Connecting a passion for beauty to CAI’s mission

By Alice Thomas Fara Homidi, a renowned makeup artist and budding entrepreneur, demonstrates through her giving that beauty is more than skin deep. Fara Homidi is a successful makeup artist whose high-profile clients include Bella Hadid, Naomi Campbell, and Billie Eilish. She’s also on the verge of launching her own line of cosmetics. But while […]

In a mountain village in Tajikistan, a new preschool brings hope and promise

In the pocket-sized mountain town of Barushan—like everywhere in the world—young children love to play, explore, and let their imaginations soar. It’s all part of the process of brain development that, under the right circumstances, can benefit a child throughout their life. But to fully capture the enormous advantages that early childhood education provides, the […]

Using education to change a life, a community, and an entire nation

By Rebecca Lee CAI Program Officer Zia Sanaban’s journey from a poor, remote village in Afghanistan to a prosperous life in Maryland is a story of hardship and struggle, perseverance and courage. Zia Sanaban grew up with three brothers in a poor rural village in Afghanistan. His family and neighbors never had enough money and […]

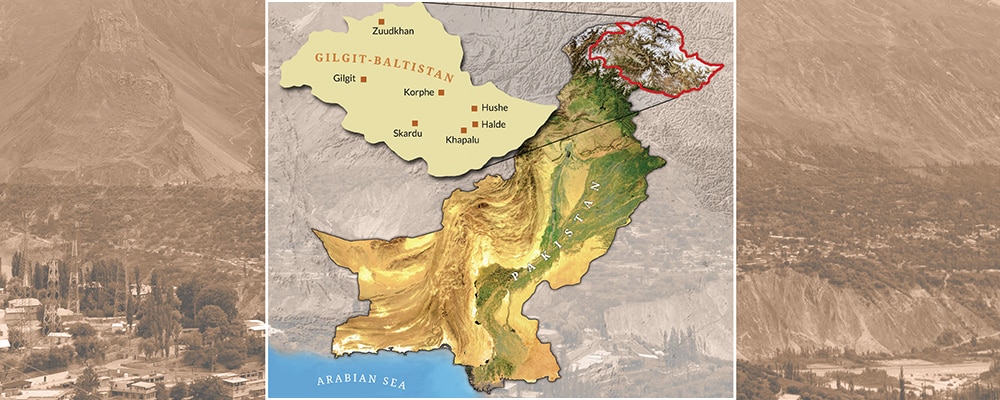

The Myths Around Menstruation Helps Girls Get an Education

By Molly Shapiro In the remote mountain villages of Gilgit-Baltistan in northern Pakistan, young girls confront many challenges in their pursuit of an education—from poverty to lack of transportation to conservative cultural norms that confine girls and women to the domestic sphere. One barrier to education that is rarely discussed—yet highly disruptive to girls’ daily […]

Kids in rural Afghanistan get the chance to attend school for the first time

By Lynzy Billing High up in the rugged mountains of Kunar province in northeastern Afghanistan, nestled between a small cluster of mud-brick homes, 6-year-old Jaweriya sat in a small classroom, carefully tracing over the letters of the Pashto alphabet with her tiny, hennaed hands. Jaweriya wakes up at 5:00 a.m. to make the one-and-a-half-hour walk […]

In remote Tajikistan, aspiring women launch their own businesses

By Molly Shapiro Imagine living in one of the most remote places in the world, in a village nestled among some of the tallest peaks on earth. It’s a place where jobs are scarce, the economy is weak, and most everyone struggles to put food on the table. And if you’re a woman, it’s a […]

Technology lights up learning in northern Pakistan

By Hannah Denys In many parts of the world, it’s unthinkable to have a classroom without technology. Lessons are projected onto smartboards where students can manipulate the information from their desks, cutting-edge calculators perform advanced equations, and children learn to code in high-tech computer labs. Yet, in parts of northern Pakistan, technology is still rare. […]

CAI donors step in to help Afghan women and children in crisis

By Alice Thomas What happens to an impoverished family in Afghanistan when the father is killed in the war or leaves his wife and children behind to work in another country? Thirteen-year-old Tamana knows. Last year, her father left to work in Iran. She lived with her mother, grandfather, and nine siblings in a crumbling, […]

Against all odds, many Afghan women and girls are still getting an education

By Hannah Denys Women and girls are standing up to Taliban rules and demanding access to education in hopes of a better future. Angiza, an eighth grader, puts on her school uniform every morning, finds a quiet corner in her house, opens her books, and studies by herself. She breaks for lunch, then returns to […]

Hope comes to Barushan

The villagers in the mountain community of Barushan in remote Tajikistan are abuzz. Old and young alike can’t stop talking about the construction of the new Preschool #2, now underway. Yusuf Sarkorov “This is the best thing that happened here in Barushan this year!” exclaims Yusuf. His son attended the former preschool which was dilapidated, […]

Fighting the new, nameless war in Afghanistan

When the Taliban retook control of Afghanistan in August 2021, 20 years after their expulsion by U.S. troops, the American War ended. During those two decades of war, 200,000 Afghans tragically lost their lives. But now, a potentially more dangerous war is brewing. This nameless war has no clear enemy. Instead, it is a battle […]

What does girls’ education have to do with climate change?

By Alice Thomas Across the globe, people are feeling the effects of climate change—from hurricanes to flooding to droughts to wildfires. Tragically, the poorest, most marginalized people are often the hardest hit. In the regions of Central Asia where CAI works, extreme weather is a part of life. But as the climate changes, poor and […]

We’re all connected

By Rebecca Lee Ask Ruth Abad for the key to the world’s problems, and she answers with one word: education. Ask her to be more specific, and she gives you this: education for girls andyoung women. “Educated girls marry later,” she says. “They have fewer children. Research shows that educating girls has a positive effect […]

Learn how to support girls’ education in smart, tax-savvy ways

Central Asia Institute depends on the commitment and generosity of supporters like you to unlock the potential of girls and women through education. Many of our supporters want to ensure future generations of children in Central Asia receive the gift of education but aren’t sure how to go about it. Here are just a few […]

Differently abled craftswoman

Now Gulnamo is 42, and she creates elaborate, richly colored handicrafts—from traditional Pamiri socks to ornately beaded jewelry to whimsical souvenirs. Making these beautiful treasures has become her passion. She’ll find any excuse—a friend’s wedding, a family member’s birthday, or just a quiet moment—to sit and practice her art. And by doing so, Gulnamo is […]