CAI Program Officer Zia Sanaban’s journey from a poor, remote village in Afghanistan to a prosperous life in Maryland is a story of hardship and struggle, perseverance and courage.

By Sonja Bahr

In the pocket-sized mountain town of Barushan—like everywhere in the world—young children love to play, explore, and let their imaginations soar. It’s all part of the process of brain development that, under the right circumstances, can benefit a child throughout their life. But to fully capture the enormous advantages that early childhood education provides, the children of Barushan must have a school.

Preschool #2, the only preschool in the village, was built in 1962 with inadequate materials and over the years, fell into disrepair. The walls and ceilings were sagging, mold was growing in the corners, coal-burning stoves used to heat the rooms belched smoke, and small children were forced to use the dilapidated wooden outhouses with no running water. Despite the awful conditions at the school, there was a waitlist to get in. When CAI staff visited Preschool #2 in 2019, it was clear that the building was unsafe and unhealthy, and that the community was in dire need of a new school.

Spring / Summer 2021:

Crews begin construction

Fall 2021:

Construction halts for winter

That’s when CAI’s generous donors stepped in. Thanks to their generosity, construction crews broke ground on a new preschool in the spring of 2021. Once completed, the two-story building will accommodate even more young preschoolers aged 3 to 5—125 children total—from the surrounding area. In addition to five classrooms, a kitchen, a nurse’s office, and art and music rooms, the new school will have central heating, indoor latrines, piped water supply, and electric power. The end result? A safe, healthy, child-friendly school where these young children can thrive and parents will feel it is safe to leave their little ones.

Following a pause in construction during Tajikistan’s brutal winter months, crews resumed their work in spring of 2022 with the goal of completing the second floor before winter sets in. The final touches, including playground equipment, furniture, and more, will be added next summer. The doors will be opened for a new class of preschoolers in fall 2023.

Spring 2022:

Construction on the second

floor begins

Summer 2022:

Construction on the second

floor continues

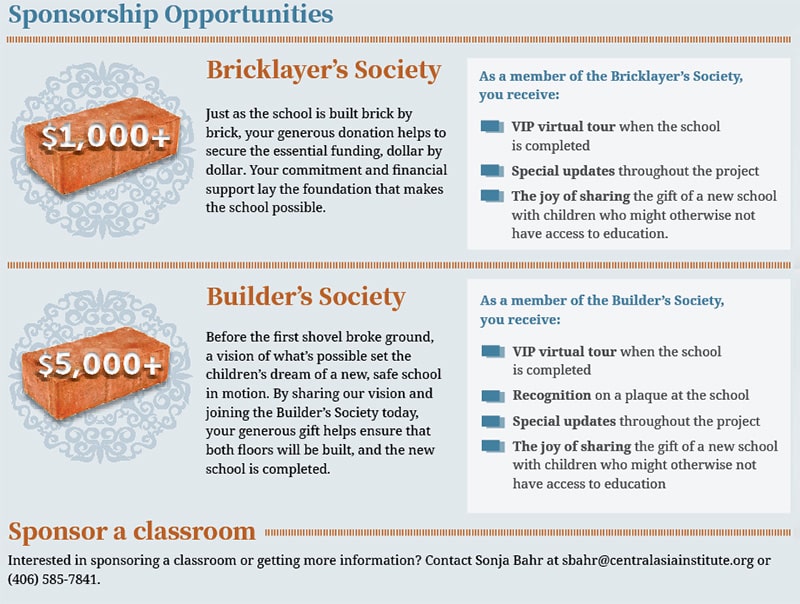

There is still time for you to get involved in this exciting project! Your support today will ensure a brighter future for generations of children to come.

And for those wishing to make a more significant investment in the school, please consider joining the bricklayer’s society by making a gift of $1,000 or the builder’s society by making a gift of $5,000. There is even an opportunity to sponsor a whole classroom. To all of you who already supported Preschool #2, thank you for bringing hope and promise to the families of Barushan!

By Rebecca Lee

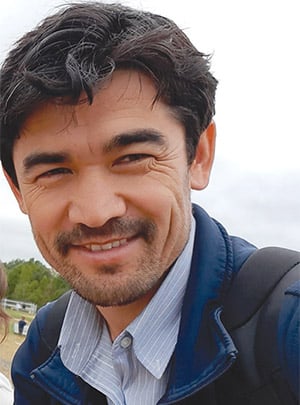

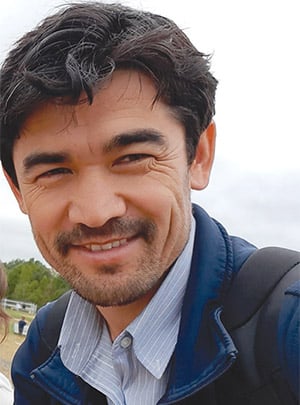

CAI Program Officer Zia Sanaban’s journey from a poor, remote village in Afghanistan to a prosperous life in Maryland is a story of hardship and struggle, perseverance and courage.

Zia Sanaban grew up with three brothers in a poor rural village in Afghanistan. His family and neighbors never had enough money and were constantly struggling to make ends meet. They had no electricity and no access to essential services. Jobs were scarce. Government aid and support systems to help impoverished families like his did not exist.

Children were born poor and stayed poor, unless they had the opportunity to go to school. “As a boy growing up, I believed education would help me overcome some of the challenges my family was facing,” said Zia. “Education would mean I could also help my community. Even when I was young, I knew I wanted to give something back to my community. I knew I wanted to help people.”

Zia dreamt of becoming a scientist or engineer so he could help tackle some of the most pressing challenges of his community. “We had no electricity. There were transportation problems and health issues. We had to walk long distances to school. There was no access to the internet or other resources,” he explained. “For me, education was something that could help me overcome some of these issues personally, for my family, and, on a broader scale, for my community.”

Zia’s mother was a strong woman who refused to accept the traditional way of life for herself and her children. She knew education was essential if her boys were to escape a life of poverty. She revered her brother and uncle—both teachers—and told her boys that these men inspired her. Her esteem and respect for teachers made an impression on Zia, one he never forgot.

Both of his parents were hard workers, but it was difficult for them to make enough money to afford school. They had to make many sacrifices to cover the fees, supplies, and uniforms their four boys required to attend classes. “My parents were kind enough to tackle all the socioeconomic challenges to help us go to school. It took their blood, sweat, and tears to make sure we were getting an education.”

To earn income, they farmed for other people and used the money to cover school expenses. Zia and his brothers rewarded their parents’ hard work by excelling at school. They also helped other students with their homework.

“Getting an education is the first step for families to be able to tackle the challenges and contribute to the development of their community,” explained Zia. “Becoming a doctor means your community will have a doctor and lower mortality rates.

Becoming a teacher means one day you can help the children of your community become educated. By getting an education, you will change the lives of your family and your village.”

The challenges that Zia’s parents faced are not unique in the rural villages of Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Tajikistan. Poor families across Central Asia encounter the same hurdles: weak or nonexistent infrastructure, scarcity of jobs, no health care, and few educational opportunities. Uneducated and without resources, the children of these villages are trapped, unless they go to school. Education is their one hope for a more meaningful, independent life.

With uncles who were teachers and a mother who put teachers on a pedestal, perhaps it was inevitable that Zia would become a teacher. He was a good student, excelling in math and the sciences, and his teachers liked him. When he was in high school, they recruited him to help teach middle school.

“This was a dream job for me—to teach and help people,” said Zia. “I learned how to deal with students, how to cover difficult topics. I was a part-time teacher. In the morning, I went to school. In the afternoon, I went to the girls’ school to teach. I learned a lot during that time. I learned how an individual can contribute by helping their peers and the children of their community.”

Zia went on to graduate from college in Kabul. He earned a master’s degree as a Fulbright scholar at Ohio University in Athens, Ohio, then returned to Afghanistan and worked for nine years in program management and career development. Back in Afghanistan, Zia was an active participant in his country’s Fulbright community.

“We were trying to make an impact,” he recalled. “We thought of ourselves as change agents to help Afghan society become a better society. We wanted to overcome socioeconomic challenges, let daughters go to school, and allow women to work.”

When the Taliban returned to power in August 2021, it imposed severe restrictions on all aspects of society, particularly on women and girls. This included limiting girls’ access to school. Despite these obstacles, CAI was able to give more than 5,700 children, mostly girls, the opportunity to go to a community-based school this past year. With the support of its donors, CAI hopes to increase that number to at least 7,500 this coming school year.

Courageous people in remote Afghan villages are ignoring the Taliban’s decrees against education and demanding their children be educated. Mothers and fathers are standing up for their daughters, insisting they go to school. They’re working to find safe spaces to house community-based schools and serving on the local councils that monitor the schools. Villagers are working with NGOs to convince government authorities that their village needs a school. Like Zia’s parents, these Afghans are passionate about their children becoming literate and having the chance to build a better life.

Unfortunately, many of the people who could have helped fight for this cause were forced to leave the country when the Taliban seized control. Thousands of educated, forward-thinking Afghans—journalists, government workers, academics, and political activists—knew they would be targeted and face persecution by the new government, so chose to flee if they could. Zia was one of those people. He and his family made it out of Kabul on August 28, 2021.

Zia’s wife was pregnant when they left Afghanistan, so their fourth daughter was born in the United States. Zia is grateful that his family is in a safe place. His daughters love school. His wife is learning English. And Zia, as program officer at CAI, is working tirelessly on behalf of the children, especially the girls, still in Afghanistan. He understands the desperation of poverty. He witnessed the sacrifices his parents made to send him to school. And he’s living proof of what can happen to a child who’s given the opportunity for an education.

In his position at CAI, Zia helps make education possible in impoverished communities that are largely overlooked by the rest of the world. “In Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Tajikistan, there are a lot of out-of-school children,” he said. “The quality of education is below standard. Access to education, job opportunities, and the outlook for careers for girls and women are all challenges. My work now directly contributes to those people by helping them get an education, pursue their dreams, and have a decent life.”

Zia is thrilled that his daughters are adapting to life in America and reaping the benefits of living in a free, open society. He recalled that in Afghanistan, it was difficult for them to even go outside. “We had a boundary wall around our house. The kids could only play inside the wall,” he said. “There were kidnappings and killings, extortion, and other things. We couldn’t let them go outside. We were contained. Here we are going to parks and we let them play. They see the freedoms and feel more secure. They’ve been able to see the world more here than in Afghanistan.”

Zia wants his daughters to become role models for the children left behind in Afghanistan. “I’m hoping my daughters find a way to be change agents and bridge these two societies,” he said. “I’m hoping they go to Afghanistan and represent the opportunities and freedoms in the U.S. When they are here in the U.S., I’m hoping they represent the Afghan people and their struggle, and that someday they facilitate a mutual understanding.”

Education gives Zia hope, and now he’s working to make hope come alive for another generation of marginalized Afghan children. “Continuing to support and promote education programs in Afghanistan is critical,” he said. “The Afghan people will remember this support. The people will feel they are not forgotten. Yes, there are issues and restrictions, but your support makes a difference.”

Become a CAI supporter and make a difference.

A gift of $100 sends an Afghan child to school for an ENTIRE YEAR!

By Molly Shapiro

In the remote mountain villages of Gilgit-Baltistan in northern Pakistan, young girls confront many challenges in their pursuit of an education—from poverty to lack of transportation to conservative cultural norms that confine girls and women to the domestic sphere. One barrier to education that is rarely discussed—yet highly disruptive to girls’ daily lives—is menstruation.

While menstrual bleeding is a fact of life for women and girls, a simple bodily function that requires proper hygiene and care, in these conservative communities, the topic of menstruation is taboo. There are many harmful myths associated with it that hamper girls’ ability to go to school, work, and participate in normal activities inside and outside of the home.

Girls and women do not talk about menstruation, and that leads to shame, misconceptions, and poor hygiene. Families restrict girls who have their period from going to school and doing chores around the house because they see them as unclean and impure. Girls are isolated and made to feel fearful about interacting with others during menses. Even when girls are allowed to go to school, their discomfort and worry about staining their clothes and their lack of access to proper sanitation facilities often make them choose not to attend at all.

To address this critical issue, one of the Central Asia Institute’s partners in Pakistan has devised a program called Menstruation Health Management (MHM) that is changing not only general attitudes but individual lives. The goal is to dispel the myths around menstruation through open discussion and education so girls can gain critical knowledge and confidence, learn appropriate self-care, and be able to continue living their normal lives when they have their period.

One of the most important aspects of the MHM program in Gilgit-Baltistan, which was launched in January 2021, is to ensure that those conducting the training are trusted by the girls and their families. “We decided to choose someone from the local community, who understands their culture and norms and speaks their language,” explained Wajeeha Ahmad, program manager. “Girls and their parents feel more comfortable talking to someone in their own language.”

Khadija is a regional coordinator in Gilgit-Baltistan who’s been doing community work for more than a decade, so she’s experienced and knowledgeable about how to establish a relationship of openness and trust. However, dealing with the taboo subject of menstruation presented new challenges, even for her.

“The first time I was in the field, it was very difficult. There was so much hesitation and shyness about having a lady come into the village to talk about this issue,” said Khadija. Still was able to break the ice by first establishing a the village. “I told them about my own personal experiences so I could build a relationship and create a space for them to share their feelings and concerns.”

Once that barrier was broken, Khadija encouraged the mothers to talk to their daughters, and then began to have sessions with the girls themselves. “The sessions make the girls more confident to talk about these issues with their mothers and the instructors. They help them overcome their fears about going out of the house when they’re menstruating.”

While discussing the feelings and emotions that surround the topic of menstruation is important, it’s also crucial to educate girls about proper care and hygiene. This not only protects their health; it also gives them the security of knowing they can handle the days of bleeding without worrying about the embarrassment of leaking or spotting.

Part of the MHM program is to provide girls with kits that contain sanitary napkins. Girls are accustomed to using cloth pads that they make at home and then wash, which can be both ineffective and unhygienic. By introducing them to sanitary napkins, they learn about healthier, more effective ways to manage their bleeding.

Because buying commercial, disposable pads each month is not feasible for most low-income households, girls are taught how to make their own pads using cotton and cloth rather than cloth alone. They are also taught how to dispose of them properly. These frank discussions and hands-on instructions further give girls the confidence that they can go out in public and attend school without fear.

The response to the program has been overwhelmingly positive, with mothers and daughters openly discussing an issue that was once verboten. “The girls didn’t even talk about it amongst themselves,” said Khadija. “Now they talk about it with their younger sisters and cousins. It’s a huge success just having them talk.”

Khadija also sees improvements in girls’ health and hygiene. “Previously, they experienced more pain and infections, and they didn’t even understand why,” she noted. “Now they know what the pain is from and how they can both prevent it and treat it. We even provide hot and cold pads to help relieve the pain.”

And of course, one of the most gratifying results of the program is an increase in school attendance among girls. “Before they would prefer to just stay home and avoid leaving their houses. Now they have their kits with a zipper and pads, so no one can see,” said Khadija. “They have their manual outlining the three steps to making their own pads, so they can go out and go to school.”

According to program manager Wajeeha Ahmad, MHM instructors also talk to girls about recognizing inappropriate touching and harassment and how to deal with them. “The instructors are trained to recognize any concerning changes in behavior among the girls,” she said.

In addition to supporting the MHM program, Central Asia Institute works to help these communities build the toilets, latrines, and washing facilities schools need to accommodate girls and ensure they feel comfortable and safe attending school. It’s all part of CAI’s unwavering commitment to helping girls get the education they need to learn, grow, and prosper.

By Lynzy Billing

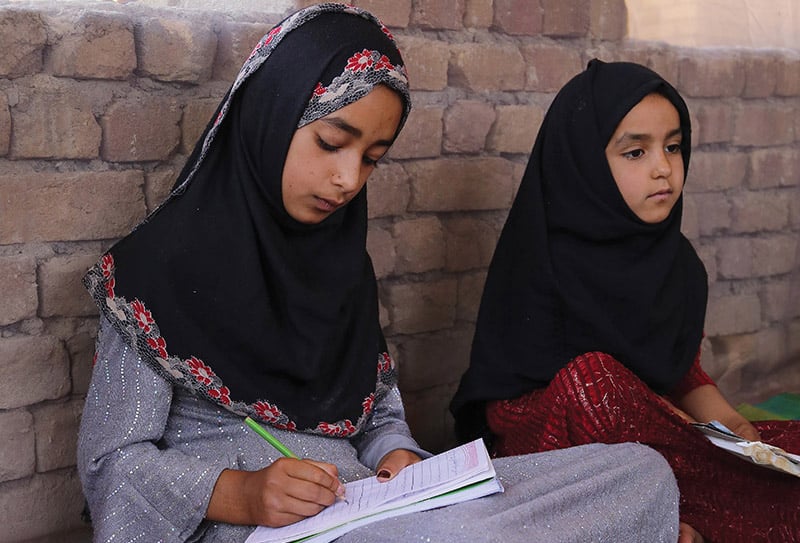

High up in the rugged mountains of Kunar province in northeastern Afghanistan, nestled between a small cluster of mud-brick homes, 6-year-old Jaweriya sat in a small classroom, carefully tracing over the letters of the Pashto alphabet with her tiny, hennaed hands.

Jaweriya wakes up at 5:00 a.m. to make the one-and-a-half-hour walk to this second-grade class in a community-based school in Spenkai village. Established in December 2020, it is the only school in the village. “We are learning the letters so if we go to the city, we can read the signs for the doctor,” said Jaweriya. “I want to learn them so I can teach my mother how to write her name.”

This community-based school is one of 49 schools established by Shining Star, one of CAI’s partner organizations in Afghanistan. Located in remote areas far from any public schools, these community-based schools provide classes for girls and boys in grades one to three who otherwise would not be attending school at all. With the support of CAI, Shining Star recruits and trains teachers and provides books, learning materials, school supplies, and furnishings. In 2022, CAI supported a total of 191 community-based schools across six provinces. In 2023, CAI hopes to expand its support to 250 communities to help meet the enormous needs.

Ten-year-old Hamidullah is another student at the community-based school in Spenkai village. “This school is very good because they gave us books and pens for our studies,” he said. “I never did any studies or had any books before because my father could not afford them. It’s the first school I have gone to, and I want to do very well in my classes because my father is not employed. But I will be a doctor.”

While the community-based schools are focused on grades one through three, the program also targets many older children who didn’t have access to schools when they were younger. For example, 12-year-old Osmania, a second-grade student at a community-based school in Spenkai village, began her schooling at age 11. That meant she was learning alongside 6-year-olds in first grade. “I talked with the elder of the village and my family and they allowed me to attend this school,” she explained.

After her school day, Osmania does her homework and then helps her mother with the chores, like washing the clothes, sweeping the floor, and looking after the animals. “Then I teach my mother what I have learnt at school,” she said. “Last night, I taught her the seasons of the year because she didn’t go to school.”

Teachers in these schools say that older students who have not received any schooling before can catch up through accelerated learning. This is particularly important for girls, who have always faced more roadblocks to getting an education and are now dealing with new restrictions under the Taliban regime. While boys at all levels have been permitted to attend school, the Taliban has blocked girls from attending secondary school (above grade six). Taliban officials have set no conditions or timeline for lifting the ban, insisting it’s only temporary. But the Taliban policy has met with resistance. In many parts of the country, tribal leaders, educators, and families are taking steps to ensure that older girls are provided with the education they need.

“I think for these older girls, accelerated learning is best, where in one year they can learn two grades,” said Kamel Farhat, deputy director of Shining Star. In 2022, CAI supported accelerated learning centers in which more than 1,200 older girls were enrolled.

Ultimately, the hope is that the Taliban will reverse the ban on girls’ secondary education. In the meantime, CAI is supporting additional programs to ensure these girls don’t fall behind in their studies, including at-home learning programs for high school girls and training courses for older female high school students who want to become teachers.

One key aspect of the community-based school model is that the entire community is involved in the creation and management of the schools. First, the school must get the approval of the village elders or mullahs—the religious leaders of the community. They also decide where the school will be located, such as in a home or a mosque. Teachers are recruited from among the local populace based on their qualifications and are provided with training. Parents serve as volunteers.

Ibrahim, who is Jaweriya’s and Hamidullah’s teacher at the school in Spenkai village, has seen how the positive effects of the school ripple throughout the community. “The parents come to me and say these children are the future of this village,” he said. “Older children from the village ask me if I can provide classes for them, and sometimes old men from the village come and sit in the back of the class with notebooks because they want to learn.

They are eager because in the past there were no options for them to learn.” Ibrahim’s students must deal with many challenges. They’re often sleepy during class because they have to get up so early to walk to school. Some are hungry and unable to focus because their parents are too poor to provide them with a nutritious breakfast. Some struggle with homework because their parents and older siblings don’t have an education and can’t help them. But despite all this, his students and their families are grateful for their community schools.

“In many ways, my students are teachers at home to their families,” said Ibrahim. “Before, when the people of this village would travel to the city or district center, they were not able to read and understand the signs for the clinic. Now they can because their children have taught them.”

With every new school that comes to a village, there are always obstacles that must be surmounted. One of the biggest is the conservative attitudes of the villagers and their long-held belief that girls should remain at home to do the housework and should never come in contact with boys when attending school. Some believe that educating girls is going against Islam.

According to Enayat-U-Rahman, a teacher at a girls community-based education (CBE) school, this couldn’t be further from the truth. “From an Islamic perspective, education is important for both boys and girls. But for girls, it is more important,” he said. “If a mother is educated, the child will learn from its mother, and she will encourage them to go to school also.”

Mohammad Gul, an imam and teacher at the CAI-supported school held inside a mosque in Kata Sang village, disagrees with the Taliban’s decision to ban girls from secondary education, saying there is no Islamic basis for it. “I told the villagers this. And they trust me because I am the imam in the mosque here,” he said. “When this school opened, many older girls came to me and asked to be enrolled in this class because there was no high school for them. The girls in this class are very sharp—even smarter than the boys.”

Mirza Mohammad, the imam at the mosque in Ashaba village in Parwan province, sees the Taliban’s decision as political and not in accordance with Islam. “Under Islam, girls have a right to education and work,” he explained. “It’s important for girls to get an education so that they and their children know their rights, including property rights and inheritance rights. More importantly, an education gives them a purpose in their lives to be someone. My daughter can choose what she wants to be in the future.”

Sometimes, the obstacles to providing an education to girls are life threatening. One man from Sondry village in Dara-I-Pech district of Kunar province described what happened when his community established a CBE school in December 2020, the first school in the village. “At the time, the Taliban was in the mountains around the government-controlled village, and they sent threatening letters to us saying that we must stop girls’ education here,” he recalled. “They said they did not want female teachers and doctors working in the village. They threatened to kill us, but we did not stop. Like my children were, I wanted all the children of this village to be educated, and that’s why we continued our work. And the community supported us also to stand against the Taliban.”

In fact, the school was such a success, even some of its most fervent critics changed their minds. “The funny thing is that now two of the Taliban that were threatening us want us to register their daughters in this class,” the man said. “They support the school now and they want secondary schools to be opened because they want girls from their own villages to be teachers and doctors.”

In the foreseeable future, these villagers will continue to face major hurdles to providing an education to their sons and daughters. They will have to deal with too few schools to meet the growing demand, along with a shortage of teachers who are qualified to teach in them. They will confront the challenge of finding the funds needed to pay teacher salaries, maintain their classrooms, and provide books and other supplies to students. And they will have to face the fact that the ruling Taliban government will continue to try to prevent girls from getting the education they want so badly. But none of these challenges will stop them from trying—and succeeding. Just one year ago, there were few schools in the remote areas of Kunar, Kabul, and Parwan. Today, some districts have up to 25.

And the kids, with the support of their families, will keep on coming. Nine-year-old Farhat attends the CBE school in Shah Wali Khel village in Parwan province along with her 7-year-old sister Kosar. “Our mother told us to come to this class,” said Farhat. “Our father went to Iran to look for work six months ago. When he comes back, I’ll show him that I can read and write. And someday, I will be able to look for work so that he doesn’t have to.”

By Molly Shapiro

Imagine living in one of the most remote places in the world, in a village nestled among some of the tallest peaks on earth. It’s a place where jobs are scarce, the economy is weak, and most everyone struggles to put food on the table. And if you’re a woman, it’s a place with many obstacles and few opportunities.

This is the Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Oblast (GBAO) region of Tajikistan, one of the poorest parts of the second poorest country in Central Asia. The villages of GBAO are isolated and hard to reach, particularly in the long winter months. And even though almost 40% of the region’s people live in poverty, the central government provides them with little help.

In GBAO and throughout Tajikistan, it’s common for men to go abroad to find work, mostly to Russia. Roughly 20% of Tajik men leave their families to work abroad, sending a portion of their earnings back home. This means that women are left alone to manage the household, take care of the children, and provide for the family’s basic needs. Sometimes, their husbands send back little, or worse, some never return home at all, choosing instead to build a new life for themselves in their adopted country.

For these poor families, having as many sources of income as possible is essential. But often women struggle to find jobs, and when they do, they often earn only a fraction of what men make. Many have marketable skills such as cooking, knitting, and sewing that could be used to make money. What they lack, however, is the knowledge, training, and experience needed to transform those skills into profitable businesses.

The ASPIRE program was launched by the Central Asia Institute Tajikistan (CAIT) in 2019 to provide the women of the GBAO region with the business know-how they need to generate income from the traditional skills they already possess. ASPIRE uses curricula and trainers from the University of Central Asia to create entrepreneurship modules in subjects such as accounting, sales, business management, and finance. It then offers a 10-day workshop to 25 to 30 female participants, teaching them things like how to design a business plan, create a budget, analyze markets, and perform basic accounting. ASPIRE also connects these women to national women’s business associations, introduces them to potential mentors, and shows them how to apply for loans.

In just a few short years, ASPIRE has already had a big impact on these aspiring female entrepreneurs, as well as their families and communities. Here are just a few examples of some of the women whose lives were changed by CAIT’s groundbreaking program.

Fakhriya Dovutova, who lives in Porshenev village of the Shugnan district, attended university but could not find work after graduating. “I was jobless and sitting at home,” she said. “It was hard to find money to get necessary things and food for my child.”

So she decided to start a business sewing and selling dresses to her friends and neighbors. “I became popular,” she explained. But when she took out a loan to expand her business, she realized that she lacked the financial literacy she needed to ensure her success.

Fakhriya asked her friends if they knew of any business courses she could take. She later got a call from a staff member at the Women Affairs Committee, telling her about ASPIRE’s 10-day workshop.

“I was not sure about doing it because I was very busy with sewing,” she said. But after attending the first day, she decided to stay for the entire workshop. “I feel I am the lucky one having the chance to attend this training. I learned how to plan my family budget, daily calculation of money and income, managing money, and saving money,” said Fakhriya. “The training changed my life.”

Just one month after the workshop, Fakhriya hired two women to help with her business. “I am teaching sewing skills and sharing knowledge with the ladies to make them successful like me,” she said. Her intention is to make sure the benefits of ASPIRE’s training don’t end with her. “My plan is to open my own sewing workshop and involve more housewives.”

Zarnisso is a mother of four children who was struggling to make ends meet after her husband went to Russia to find work. Things got very difficult during the pandemic because her husband wasn’t able to send money home. Zarnisso went to Russia herself to try to make money but couldn’t bear to leave her kids at home alone. “Life was hard,” she remembered.

Zarnisso knew that she had many skills that could be lucrative—including sewing, knitting, baking, cooking, and gardening—but she didn’t have the seed money or the knowledge needed to start a business. Fortunately, she did have the support of her fellow villagers, one of whom told her about ASPIRE and offered her the chance to attend the workshop.

“During the 10 days I felt that I am one of the skillful women with craft skills,” she recalled. “In the training, all my fear and worry had gone. I decided to take a risk and bravely started to bake kulcha.” Zarnisso took the round flatbreads to a local shop to be sold. With the money she earned, she bought more flour so she could bake more bread. “In this way, I increased my income,” she explained. “I started to save money for my children’s needs, as we learned in the training.”

“I feel a great improvement in my life,” Zarnisso said. “I am sharing the training information with my children, who help me in making kulcha. I am planning to get a better oven to make quality kulcha, as there is big demand.” Already, Zarnisso is receiving a lot of orders from neighbors and friends who want her kulcha for weddings and other events.

Lojvar lives in Sharikkhona village in the Shugnan district. Like the other villagers, she and her family have a small plot of land, but it wasn’t enough to sustain them. When she married her husband, he wasn’t working, so they didn’t have enough money to buy food. But despite her troubles, Lojvar said: “I am a happy woman because I have crafting skills learnt from my grandmother and my mother.

I was involved in knitting, weaving, and doing other traditional things for weddings with my mother.” Lojvar was new to the village, so she wasn’t comfortable selling things to her neighbors, who weren’t yet aware of her talents. Instead, she made products and sent them to her mother in another village to sell. But things changed after she attended the ASPIRE workshop.

“Luckily, after attending the training I got courage. My fear disappeared, and I gained enough finance literacy,” she said. “Today, I am freely selling milk and making Pamiri socks and slippers from natural wool. My plan is to get a new machine for weaving and spinning.”

Like other women who participate in the ASPIRE program, Lojvar wanted to impart her learning to others and inspire them to achieve their dreams. “As we learned from the training, I want to become a successful woman and teach others, too,” she said. “Therefore, I am planning to open a mini workshop and create jobs for other housewives in my village.”

Thus far, 170 women from GBAO have received training through ASPIRE, and 119 of them have started businesses selling products such as clothing, mattresses, pillows, socks, slippers, and bread. But there are many more women who want to take part in this type of training, and CAIT’s goal is to meet that growing demand.

Looking ahead, CAIT intends to offer this training in more districts to more women, supplementing the courses with increased financial support and mentoring opportunities for graduates.

The importance of doing this work is clear. For women like Fakhriya, Zarnisso, and Lojvar—women who had nowhere else to turn in their time of need—ASPIRE has succeeded in transforming their lives. This groundbreaking program has provided hope and stability to their families, and it has bolstered the economy and living conditions of their entire communities.

By Hannah Denys

In many parts of the world, it’s unthinkable to have a classroom without technology. Lessons are projected onto smartboards where students can manipulate the information from their desks, cutting-edge calculators perform advanced equations, and children learn to code in high-tech computer labs.

Yet, in parts of northern Pakistan, technology is still rare. Many schools in these isolated, mountain villages don’t even have electricity. And because they never learn how to turn on a computer, use a smartphone, or search the web—basic tasks in today’s tech-savvy world—hundreds of thousands of Pakistani children are being left behind.

But the good news is, Central Asia Institute is determined to help these kids and their communities catch up.

Arando village is the last human settlement in northern Pakistan’s Basho Valley. Heavy snowfall, avalanches, and washed-out roads can cut the village off from the rest of the world for up to seven months at a time. Despite the harsh conditions, 180 families eke out a living in this high-mountain wilderness, farming and raising livestock to stay alive. Without a school, Arando had the highest number of out-of-school girls in the district for many years. That changed in 2021, when CAI established a community-based school in the town. But since power lines couldn’t reach the village, there was no electricity, so students struggled to read their papers and see the blackboard.

Fortunately, CAI donors came to the rescue. With their support, CAI was able to bring electricity to the school through a small solar array that was connected to the school building. Students can now read their lessons in the bright classroom without squinting in the darkness. Everyone in the community is excited about what this means for the future. “Now our girls can get an education and become teachers, doctors, and engineers,” said one father, Mehdi Ali.

Arando was one of six isolated mountain villages to receive solar power thanks to the support of CAI donors. An additional 13 schools received battery-powered generators. These schools have sporadic access to power, so the batteries charge while the electricity is flowing—typically just three or four hours a day. Then, the batteries are used to light the classrooms during power outages.

Getting electricity to classrooms and turning on the lights was just the first step. After that, 64 community-based schools in these remote mountain villages received computer tablets preloaded with three months’ worth of lessons, games, and videos. An additional 15 schools received USB sticks loaded with information and televisions to project the materials.

“In this town, technology was never used in school before,” said Seema, a teacher at a girls’ primary school in Gilgit, Pakistan. “Due to this, students received a lot of benefits and were interested in the lecture because of the videos, pictures, and much more.”

New lessons are loaded onto the tablets and USB sticks every few months, making it easy for schools in places without internet connectivity to access up-to-date materials. An online game and quiz app designed to help children learn was also piloted in these villages. In December 2021, 150 students started testing the app. In the future, CAI hopes to give more students access to the program if it performs well.

These tools enable students to explore new subjects and deepen their understanding of difficult concepts. At the same time, they increase engagement and make learning fun. Visual learning aids like videos can help students better understand and retain ideas. Researchers have found that people don’t remember things they hear nearly as well as things they see.

Getting comfortable with technology while they’re young will go a long way towards helping these children connect with the wider world, apply to university, find professional jobs, and adapt to this ever-changing digital world.

Teachers in these tiny mountain villages are responsible for guiding students on their path towards technological literacy. But before these e-learning programs were introduced by CAI, many of them had never used a computer or tablet. Some had never even owned a phone. They relied on travelers to take handwritten letters to friends and relatives in nearby towns.

To make them comfortable with their new tools, CAI organized a training where teachers were walked through everything they needed to know step by step—from turning on a tablet or television to opening a browser to playing videos or audio recordings.

After the training, WhatsApp groups were set up so the teachers could communicate with one another and ask questions of support staff. Even though this type of connectivity was new to these educators, they made great use of their new resources. The WhatsApp groups have been especially effective, allowing teachers to reach out to one another to problem solve, exchange ideas, or share words of encouragement.

For teachers with more technological know-how, CAI offered an online teacher training program. Introduced several years ago, it was designed to help teachers in remote villages continue their education from home. They’re able to learn at their own pace by watching videos and completing reading assignments. Graduates receive a certificate from an accredited university, and credits from the course can be applied towards a university degree.

The program was introduced at an opportune time. Soon after its launch, the COVID-19 pandemic emerged, making it impossible to hold in-person courses. The online program was invaluable in allowing teachers to continue their studies without interruption. The first wave of 30 teachers have successfully completed this program and were awarded certificates.

While northern Pakistan still can’t be described as a technology hub, slowly but surely, change is happening. For the first time, teachers and students are being exposed to technology, and that technology is opening the door to the larger world outside of their isolated mountain villages.

“One year, two years, or even three years of technology education is not enough to change a life as much as we want,” said Wajeeha Ahmad, assistant manager at CAI’s Pakistani partner organization. “But the initial idea—how tech can be used in school—has begun. Now teachers know that they can use books and technology. And students are absorbing content differently when they see it on screen. Baby steps and sticking with it over the long term—that is how change will happen.”

By Alice Thomas

What happens to an impoverished family in Afghanistan when the father is killed in the war or leaves his wife and children behind to work in another country? Thirteen-year-old Tamana knows.

Last year, her father left to work in Iran. She lived with her mother, grandfather, and nine siblings in a crumbling, damaged home. Twelve people shared one room and a kitchen with no door, window, or proper roof. Cooking was difficult when it rained or snowed. Her mother begged at the village bakery for bread to feed her children. Tamana finished one year of schooling before the family ran out of money to buy her books, notebooks, pens, and school uniform. She hasn’t been back.

Tragically, Tamana’s situation is not unique. Since the Taliban retook control of Afghanistan more than a year ago in August 2021, the humanitarian crisis in the country has worsened dramatically. Thousands of families don’t have enough food to eat, and a shockingly high number of children are suffering from severe malnutrition. Hundreds of thousands of people were displaced by the fighting during the summer when the Taliban took control. Families forced to flee their homes with only the clothes on their backs went to squalid, crowded displacement camps. The majority were women and children.

Shortly after taking power, the Taliban put in place harsh restrictions on women’s ability to work outside the home, putting female-headed households like Tamana’s in dire straits. When mothers are forced to stay at home with their children, they have no way to earn income.

The plight of Tamana’s mother Rahila, who must raise her destitute family by herself, is heart wrenching. “I am spending my entire life struggling so hard to find a bite of food for my daughters,” she said.

Last winter, the situation grew especially dire for the most vulnerable, including displaced and female-headed households. As the frigid temperatures set in, the poorest families were without fuel to heat their homes, proper clothing to keep them warm, and money for medicine when someone got sick. The COVID pandemic only deepened the economic crisis.

Thirteen-year-old Sumaya lives with her parents and two sisters. Her father suffers from a chronic mental disorder and is unable to work. Her mother sometimes does laundry and housework for other families, but no one is earning a consistent income. Their home is in poor condition. They’re frequently late with the rent and without money to buy food and household supplies.

Sumaya went to school through grade five, but now the family cannot afford her school supplies and uniform. Sumaya would love to become a doctor and help others, but she has no idea what her future holds. She and her family live in a chronic state of uncertainty.

While women still dream of providing an education for their children, often they can only focus on getting by. When they have been left to raise their children by themselves, unable to leave home to find work, they struggle just to keep their family fed, sheltered, and warm.

Thanks to your support, last winter we were able to give hundreds of families the emergency aid they needed most. Looking to the future, we remain nimble, acutely aware that the situation in Afghanistan is volatile. We need to be ready to act quickly and respond appropriately in an emergency.

With the Taliban back in power and the economy in shambles, millions of people remain in crisis. Emergency mode—at least for the foreseeable future—appears to be the new norm. But with your continued support, we know that Afghans, like Tamana and Sumaya, have a fighting chance.

By Hannah Denys

Women and girls are standing up to Taliban rules and demanding access to education in hopes of a better future.

Angiza, an eighth grader, puts on her school uniform every morning, finds a quiet corner in her house, opens her books, and studies by herself. She breaks for lunch, then returns to her books until what would be the end of a normal school day in Afghanistan. Even though the Taliban has closed schools for adolescent girls like Angiza, she is not putting down her books or lessons. Even if she must do it alone, she is determined not to give up her education.

Across the globe, women and girls like Angiza are losing their basic freedoms. Nowhere is the threat more daunting than in Afghanistan, where the Taliban, back in power since August 2021, is attempting to not just repress girls and women, but to render them invisible. In a series of oppressive and misogynistic rulings during its first year back in power, the Taliban has attempted to destroy the lives of women and girls by denying their rights to education, employment, and free movement. It has decimated the country’s system of protection and support for women fleeing domestic violence; beaten or imprisoned women and girls for protesting new restrictions; and contributed to a surge in the rates of child, early, and forced marriages.

Topping the list of human rights being targeted by the Taliban is access to education. An uneducated population serves the Taliban’s agenda. Uneducated women are less resistant to staying at home and remaining illiterate and subservient. Uneducated boys and men are fodder for recruitment. A girl with a book or a professional woman unafraid to speak out in protest undermines the Taliban’s power.

“These draconian policies are depriving millions of women and girls of their right to lead safe, free, and fulfilling lives,” said Agnes Callamard, Amnesty International’s secretary general. “Taken together, these policies form a system of repression that discriminates against women and girls in almost every aspect of their lives. Every daily detail—whether they go to school, if and how they work, if and how they leave the house—is controlled and heavily restricted.”

Amnesty International reports that rates of child, early, and forced marriage in Afghanistan are surging under Taliban rule. Destitute families are being forced to marry off their daughters in exchange for a “bride price.” In a country suffering from widespread hunger, where 90% of the population now lives in poverty, one less child at home means one less mouth to feed.

But the people of Afghanistan are not giving up on their quest for an education. They know that providing an education to both boys and girls is not only their child’s best chance for a better life, it’s also the best hope for the future of their family and their country.

Afghanistan has made huge strides in educating its youth over the last 20 years. Back in 2001, when the Taliban’s last rule ended, virtually no girls were enrolled in school. In August 2021, when the Taliban took back control and the United States withdrew from the country, 3.5 million girls were enrolled in school. During that 20-year span, literacy rates among girls doubled from 20% to 40%.

Without the international community’s continued support for education, these hard-fought gains could be lost, and the next generation of Afghans, especially women, could lose out on education altogether.

“Education is hugely important to the future of Afghanistan,” said Alice Thomas, executive director of the Central Asia Institute. “With 63% of the population under 25 years of age and 46% under age 15, education has the potential to one day save the country from endless cycles of conflict and repression.”

Over the past two decades, CAI has worked to make education possible, especially for girls living in impoverished, rural areas where more than half of girls were out of school even before the Taliban regained control. Our focus is on those remote communities with the largest number of out-of-school children.

Because there is often no government-run school in these areas, CAI’s approach is to bring education directly into the heart of these communities by establishing community-based schools. The community-based model means classes are held in the home of a village elder, in a mosque, or in a similarly safe space in the village. Involving the community is imperative. A council comprised of members who are elected by the people of the village recommends teacher candidates and monitors the school. Because the council has agency over how the school is run, the members take ownership in making the program a success. If problems arise with the Taliban, the council does the negotiating.

“In many ways, CAI’s approach of working through local partners and engaging the local community to ensure buy-in has helped us adapt to the new challenges,” Thomas explained. “The communities themselves drive the demand for education, and when obstacles arise with the Taliban, they are willing to go to bat for their children.” It takes tremendous courage to stand up to the Taliban, yet ordinary Afghans are fighting back, demanding education for their children, including their daughters.

Even though some council members may not be able to read and write, they recognize education as their children’s only hope of one day moving on from a life of hardship and struggle. They’re passionate about defending the program that is educating their children. This past year, CAI employed the community-based school model to provide education for approximately 5,700 children, primarily girls, in grades one through three in nearly 200 rural communities across five provinces. Next year, CAI hopes to increase that to 250 community schools that will serve approximately 7,500 children, primarily girls.

CAI is also piloting projects to reach adolescent girls whose schools the Taliban has refused to reopen. Again, the approach is to work closely with the community to recruit teachers and find a place to hold private lessons for the girls. Another project involves recruiting older high school girls to become teachers for the younger classes. The programs are in high demand among parents, communities, and the girls themselves. CAI is now working with its partners to expand these classes in 2023 to reach even more adolescent girls and help ensure their education and path to a better future are not taken away.

“We’re slowly making inroads—one girl, one boy at a time,” said Thomas. “Positive change is possible if the population is educated.”

In 2022 CAI supported

191 community-based schools across five provinces,

serving 5,700 children, primarily girls.

CAI’s 2023 goal is to expand the number of community-based schools to 242

and educate 7,500 Afghan children.

Over the past 20 years, a whole generation of Afghan women have been educated. Their enormous contributions to their families’ welfare and to Afghan society have led to a shift in public attitudes towards girls’ education, and not just in urban areas. Data collected by UNESCO, World Health Organization, UNICEF, and other organizations show a remarkable improvement in the life outcomes of an educated girl and the choices she makes compared to her uneducated counterpart. Today, a large majority of Afghans—87% according to a 2019 survey by the Asia Foundation—support girls’ education.

The ability to earn an income is one incentive for getting an education, but there are many more. An educated young woman marries later. She’s older when she has her first child, and she’s likely to have fewer children. Because she sees how much better her life is than the life of her uneducated mother, she is determined to send her own children to school, especially her daughters.

An educated mother can find work and earn income, which means the family has a place to live and food to eat. Her children are healthier. And when a child gets sick, the family can afford medical care. On every measure of quality of life, including health outcomes, personal safety, and economic indicators, educated girls surpass girls who never had the opportunity to go to school.

“In a country riddled with chaos and poverty, education gives girls and women a fighting chance,” said Thomas. “It offers a ray of hope—a beacon pointing to a better life. Education gives girls and women the power to make their own decisions, earn income, and contribute to the well-being of their families, communities, and country.”

“Many things give me hope about Afghan women,” said Duniya Stanikzai, former deputy director of Shining Star, one of CAI’s partners in Afghanistan. “Afghan women are not the same as they were 20 years ago; they have changed. Back then, women were silent and afraid and accepted whatever the Taliban said. Now they’re finding ways to create opportunities for themselves.

“Girls in secondary school who can no longer attend classes due to the Taliban’s restrictions are learning online or in secret schools,” said Stanikzai. “That women are finding ways to work around the Taliban indicates how desperate they are to educate the daughters and adult women in the family. We don’t want the Taliban to win.”

CAI is committed to standing with Angiza, Stanikzai, and so many other courageous Afghan women and girls like them who are fighting for their lives. Never before has CAI played a more important role in their futures.

“Education changes lives, protects futures, unites communities, and kindles hope,” said Thomas. “These are enormously challenging and deeply troublesome times for Afghanistan. But we’re adapting and adjusting our programs to provide education to youth. With your help, we will continue to give girls and women the one thing that no one, including the Taliban, can take from them: an education.”

A $100 donation sends an Afghan child to school for an entire year.

The villagers in the mountain community of Barushan in remote Tajikistan are abuzz. Old and young alike can’t stop talking about the construction of the new Preschool #2, now underway.

Yusuf Sarkorov

“This is the best thing that happened here in Barushan this year!” exclaims Yusuf. His son attended the former preschool which was dilapidated, drafty, and horrifically unsafe.

“To all those who helped us and made a decision on this construction, huge gratitude from the residents of Barushan!”

Yusuf’s enthusiasm is shared by other parents, children, and teachers alike.

“The whole village is very, very happy,” says Nuriya Tavakalova, the head of the school. “Every day, passing by the construction site, people observe the construction process and are very happy that the work is progressing at such a speed.”

A new school is a big deal in a remote, impoverished village, where families can feel cut off, isolated, and forgotten by the rest of the world. Education represents the chance for a better life. A new school instills a sense of pride and ownership in the community. Their enthusiasm and sense of pride are contagious – we feel it and hope you, as a supporter, can feel it too!

The old school provided places for 112 children ages 3 to 6. The new two-story building will be large enough to accommodate the children on the waiting list, bringing the total to 130 children—an increase of at least 15 percent!

We’re projecting that enrollment will continue to grow as the area grows in population. The new school will also serve the young children from a nearby village.

But of equal importance is what the new school will mean for the community over the span of several years. By giving young children the advantages of an early start on education, the preschool will contribute to the long-term well-being of the entire village.

Future generations will receive a foundation for learning. Children who attend early childhood development activities like those that will be offered at Preschool #2 are likely not only to perform better in primary school and but also complete high school. And because children are more likely to stay in school when they start at a young age, the odds of them one day earning a living wage and contributing to their country’s economy also improve.

Rustam, an education specialist and local resident, echoes the cries of joy from her community. “We residents of Barushan village express our gratitude to CAI for such a gift to our children and our future as a whole!”

From the onset we knew that building the school would be a multi-year undertaking. Thanks to the generosity of donors like you, we were able to raise the funds for the first phase of construction. We’re pleased to report that progress is going well.

As of mid-June, the rebar is set and most of the foundation has been poured. Framing and backfilling are underway. Weather conditions have been favorable this spring, which is a huge plus in a part of the world where weather complications as well as earthquakes and landslides can halt construction for weeks. Barring any unforeseen glitches, the contractors are on track to finish the first floor before winter sets in.

Preschool #2 has major upgrades!

Remember Qurbonbegim? She’s the little girl we featured in our fundraising campaign. Thanks to donors like you, Qurbonbegim’s dreams of a school where the walls are not crumbling, and the rooms are not cold, are coming true.

While Qurbonbegim has finished preschool, and will be going on to primary school after summer vacation, her enthusiasm for the new Preschool #2 hasn’t waivered.

“I am happy that the construction of the new preschool began because my brother is four years old. I will take him to preschool when (the school) is ready.”

Qurbonbegim

We join Qurbonbegim and the villagers of Barushan to express our thanks for your support. It takes courage to dream big. Thanks for stepping up and dreaming with us.

To continue your investment in Preschool #2, go here if you wish to donate to the second phase of construction. Thank you!

When the Taliban retook control of Afghanistan in August 2021, 20 years after their expulsion by U.S. troops, the American War ended. During those two decades of war, 200,000 Afghans tragically lost their lives. But now, a potentially more dangerous war is brewing. This nameless war has no clear enemy. Instead, it is a battle of survival for the Afghan people.

Throughout the spring and summer of 2021, a third wave of COVID spread across the country like wildfire. With limited ways to protect themselves, a lack of understanding about the virus, and virtually no access to the vaccine to prevent it, countless Afghans succumbed to illness and death. When the Taliban seized power in August, the battle for survival intensified.

Government services and international aid have all but ceased leaving Afghanistan’s economy on the verge of collapse. Only 5% of households report they have enough food to eat, and with winter fast approaching, the outlook is grim. Most at risk are more than 400,000 women and children who have been displaced since the beginning of 2021. Penniless, homeless, and with no way to support themselves, they are on the frontlines of this new, nameless war.

Of the approximate 550,000 Afghans displaced in 2021, about 80% are women and children.

Thanks to your generous support, to date, Central Asia Institute has helped thousands of the most vulnerable Afghans. To combat the spread of COVID, you’ve helped provide:

In addition, women-led families and female students in Takhar and Kapisa provinces benefited from 13,700 handwashing stations and 12,160 facemask kits. And loudspeaker messages about COVID-19 were broadcast in camps for displaced people to decrease infection rates and encourage social distancing and proper hygiene.

Around 18 million Afghans, almost half the population, are now in urgent need of humanitarian assistance, according to the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. Unfortunately, the need will likely increase.

At Central Asia Institute, we’re doing everything in our power to assist communities affected by the crisis. In the coming weeks, we’re planning to distribute an additional 300 bedding kits (blankets, tarps for shelter, etc.), 300 hygiene kits (soap, menstrual hygiene products, etc.), and 300 education kits (books, pencils, etc.) to displaced families.

Nearly 18 million Afghans, almost half the population, are in urgent need of humanitarian assistance.

The crisis in Afghanistan cannot be explained through statistics alone. Hearing from people like Aisha, whose heartfelt letter opened the Journey of Hope magazine, is the best way to understand the situation. So we thought it was only right for her words to close the magazine as well.

Hello and salam (peace) to the world. My name is Aisha, and I’m 21 years old. I am one of the displaced people who fled from Kapisa to Kabul. By the time I am writing this, the Taliban have captured Afghanistan—my country! Now girls are being forced into marriage, female workers marched away from their jobs, and activists' homes raided in a clear message that the freedoms of the last 20 years are coming to an end. I'm worried about my future. I won't be allowed to get an education, work, go outside, or live the life I want. I feel like I am in prison without having committed a crime. For this new generation of Afghan girls, who grew up going to school and nurturing unfettered dreams, the Taliban era is ancient history, and turning back the clock is a nearly incomprehensible fate. Please, do not leave us alone. We have not forgotten the help that other countries offered us in the past, and we will not forget any help you offer us now. Please release us from this prison. Please help my people. Please help Afghanistan!

- Aisha

The situation in Afghanistan is changing rapidly. Please visit centralasiainstitute.org for the most up-to-date information about what’s happening on the ground and our efforts to support the Afghan people.

By Alice Thomas

Across the globe, people are feeling the effects of climate change—from hurricanes to flooding to droughts to wildfires. Tragically, the poorest, most marginalized people are often the hardest hit.

In the regions of Central Asia where CAI works, extreme weather is a part of life. But as the climate changes, poor and vulnerable communities are finding it harder to cope. Adding to the problem is that governments in this region have limited capacity to prepare for and respond

to disasters.

For example, Afghanistan is currently facing a severe drought that comes on the heels of the 2018-2019 drought. As of early September 2021, some 7 million Afghans who depend on agriculture and raising livestock to survive required humanitarian assistance.i With lower-than-usual harvests expected this fall, Afghan farmers are bracing for the worst this winter. Even before the government fell to the Taliban, former President Ashraf Ghani acknowledged that the government lacked the funds and capacity to manage the impending crisis.

While climate change is impacting all regions in the world, ecologically fragile, high-mountain areas face unique risks. Nowhere is this more evident than the remote and mountainous areas of Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Tajikistan, where CAI has long focused. The Pamir, Karakoram, and Himalayan ranges are part of the broader Hindu Kush Himalayan (HKH) region, which is known as the “Roof of the World” because it has some of the tallest peaks on Earth. Many are covered with deep glaciers and serve as water towers on which billions of people living in the broader Asia region depend for fresh water and food.

But in recent years, warmer temperatures have accelerated glacial melting, resulting in more intense flooding and, over the long term, depletion of water sources. The United Nations recently warned that even conservative scenarios for future global warming indicate that the region will lose one-third of its ice volume by the year 2100.ii

“I have noticed that the number of glaciers is decreasing, and the glaciers are melting and causing natural disasters like mudslides,” explained one senior geologist from Tajikistan who helps communities prepare for the effects of climate change. “The water level of the rivers is getting higher, washing out the roads and the crop fields.”

Farmers in the region are noticing the changes as well. Gulru and her family have been farming their plot of land for more than 60 years. “The climate has changed a lot,” she said. “Before we had very good harvest from our little field, but this year our field was destroyed by a mudslide. Then, after we cleaned the field and planted vegetables, the harvest was not good. There wasn’t enough rain and all the crops dried up. So, this year we have to buy our vegetables from the market.”

In the HKH region and other poor and ecologically fragile parts of the globe, women and girls bear the brunt of extreme weather and climate change. Poverty and other economic, social, and cultural factors act to heighten their vulnerability to climate change impacts. At the same time, they have far less access than men to the resources, knowledge, and decision-making that would help them to recover and adapt.

For example, when disasters like flash flooding or typhoons occur, women and girls are far more likely to be killed or displaced. Females living in displacement camps also face a heightened risk of sexual exploitation and abuse.

In the case of long-term disasters like droughts, socio-cultural norms and childcare responsibilities can prevent women from migrating to urban areas to seek

assistance or find jobs. When food is scarce, mothers often forgo meals so that the males and small children can eat. They must also travel greater distances to get water, increasing the risk of

gender-based violence.

Climate-related disasters have also been shown to contribute to a rise in early childhood marriages by exacerbating poverty and incentivizing families to marry off young daughters. Girls are also more likely than boys to drop out of school when their families are facing environmental crises.

The same social, economic, and cultural factors that make women and girls more vulnerable to extreme weather often prevent them from participating in solutions.iii Because women in the remote communities CAI serves are often illiterate and lack resources, they are less equipped to adapt to climate change. And because they aren’t included in decision-making and planning processes, they are unable to participate in devising climate solutions.

The good news is that research shows that educating women and girls may be one of the best ways to overcome these problems. Education not only opens the door to more opportunities, it also allows women to be better stewards of the environment while building their resilience to extreme weather and the impacts of climate change.

In addition, education plays an important role in promoting female reproductive health and rights. Studies show that women who are educated have healthier births and greater control over their bodies. They can better decide when to have children and how many to have. According to Project Drawdown, a nonprofit organization that works on climate solutions and research, “Estimates suggest that together with family planning, girls’ education has the potential of avoiding nearly 85 gigatons of carbon emissions by 2050.”iv That’s a big reduction considering that in 2020, global carbon emissions from fossil fuels were 9.3 gigatons.v In fact, Project Drawdown includes girls’ education as one of the top 10 strategies for combating global warming.

Another factor supporting girls’ education as an effective strategy for addressing climate change is that women have been shown to make excellent environmental leaders. Studies have linked female leadership, which obviously requires education, to better environmental policies and decreased climate pollution.

When looking to the future, it’s also critical to ensure that girls and women get the education, training, and skills they need to prepare themselves for green jobs in the new green economy. This will require not only enabling girls to participate in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) education, but also developing their empowerment skills and helping them actively participate in decisions affecting the societies in which they live.vi

In the countries where CAI works, access to quality education is limited, especially for girls. Afghanistan and Pakistan have some of the highest rates of out-of-school children in the world, and the majority of them are girls. In Tajikistan, girls tend to drop out before reaching high school at a higher rate than boys, and fewer girls complete their secondary education and attend university.

With the support of our dedicated donors, CAI is working to increase girls’ and women’s access to quality education. But making educational opportunities available to girls and women serves a much broader purpose. For girls and women, education is key to unlocking their full potential. It empowers them to thrive. And when girls and women thrive, so do their families, communities, and countries.

We know that tackling climate change can seem like a huge, unsolvable challenge. Yet we know that advancing girls’ education is a proven strategy for helping to solve many of the world’s other, seemingly unsolvable problems – such as poverty, poor health, and insecurity. The same holds true for humankind’s greatest challenge – climate change. We know, as you do, that when you educate a girl, you truly are changing the world!

i. McCarthy, J. (2020, March 5). Change Impacts Women More Than Men. In Global Citizen.

United Nations. (2021, August 16). Five ways climate change hurts women and girls. In United Nations Population Fund.

ii. Policy Brief: Melting Glaciers, Threatened Livelihoods: Confronting Climate Change to Save the Third Pole (2021, June). In UNDP.

iii. Osman-Elasha, B. (2013). Women…In The Shadow of Climate Change. In UN Chronicle.

iv. Hawken, P. (2017). Drawdown: The Most Comprehensive Plan Ever Proposed to Reverse Global Warming.

v. Mkitarian, J. (2020, December). 2020 Global Carbon Budget. In Global Ocean Monitoring and Observation. https://globalocean.noaa.gov/News/2020-global-carbon-budget-released-1

vi. Kwauk, C. (2021, February). Why is girls’ education important for climate action? In Brookings.

By Rebecca Lee

Ask Ruth Abad for the key to the world’s problems, and she answers with one word: education. Ask her to be more specific, and she gives you this: education for girls and

young women.

“Educated girls marry later,” she says. “They have fewer children. Research shows that educating girls has a positive effect on their health outcomes, on their economic opportunities—I could go on and on.”

Ruth learned early in life that when a family has limited resources, the boys get priority. She sees that dynamic at play in Central Asia.

“I’m 76 years old,” she says. “I graduated from high school in 1962. My parents planned to pay for college for me and my brothers, but the message was, if the money runs out, the boys will go because they will have to support a family.”

Thankfully, the college money lasted, and Ruth earned a teaching degree.

“I went into elementary education when women had three choices for a major: nursing, teaching, or social work.”

While she was teaching, Ruth volunteered in support of women’s rights and eventually decided to pursue a career in public health.

“I naively applied to several schools,” she recounts. “One was the University of Hawaii. As luck would have it, that year the federal government offered fellowships to students in public health as part of an initiative to improve the public health infrastructure in the U.S. In 1975, the government paid my tuition at the University of Hawaii and gave me a small stipend to live on.”

“Imagine,” she says with disbelief, “a girl from New England goes to graduate school in Hawaii! I’ve always been appreciative and grateful for that experience.”

Gratitude comes up often in conversation with Ruth. “More and more,” she says, “I realize how privileged I am. I’m not wealthy. We’re a middle-class family, but I had the chance to get an education. I’ve had good health care. It breaks my heart that others don’t have these same advantages. It’s wonderful that organizations like Central Asia Institute come in and help communities educate girls.”

Ruth’s interest in Central Asia Institute began with Greg Mortenson’s book, Three Cups of Tea. “That book opened my eyes,” she says. “I found

it amazing.”

The book piqued her interest in that part of the world. Some years later, she heard Mortenson speak at the local high school. He echoed her belief in the power of education, especially for girls and women. She left the event knowing she wanted to support organizations that support women and children.

“It’s just not fair,” she says. “Some people, because of where they’re born and who their parents are, have more benefits and privileges than a person living someplace else. It’s just not right.”

“I live in my own little community,” she explains. “I have contact with my grandchildren, and with friends who have similar values and do the same kinds of activities.” But by supporting CAI, Ruth feels more connected to the world.

“I’m learning that we’re all connected. If part of humankind is suffering, it affects all of us. We can’t live in a bubble.”

When her granddaughter was born, Ruth decided to put money away every year for her education. Through small gifts at Christmas and birthdays, and contributions to her granddaughter’s education fund, little by little she is ensuring that her granddaughter has the resources to pursue an education no matter what.

Now that her granddaughter is a little older, Ruth has begun talking with her about the plight of children in other parts of the world. Although her granddaughter is only 7, Ruth wants her to be aware that not every girl is as lucky as she is to be born in the United States, go to a good school, have plenty to eat, and see a doctor when she’s sick.

“I show my granddaughter the Journey of Hope magazine. We look at the photos together. We look at the girls in their schools and talk about their situation. The magazine provides an educational opportunity for me to talk with her about what it’s like to grow up in a poor village. I hope I’m slowly helping her understand that not everybody has all the privileges that she has.”

“This little girl has everything she needs,” Ruth explains. “Other girls don’t have that same opportunity. Their families don’t have the resources. Giving to CAI is my small way of equalizing that.”

“‘I give you money,’ I tell her, and I also give to girls on the other side of the world. I’m not heavy handed about it, but little by little, we talk about these things.”

Ruth’s message to other CAI supporters and folks hearing about CAI for the first time is this: “I would tell them that CAI is a well-run organization. They make you feel like you’re making a difference. The money goes where there’s a need. If we want to make

a difference in the world, we need

to provide education to girls and young women.”

Ruth encourages grandparents like herself or aunts and uncles who are helping family members with an education fund to think of other girls and children who don’t have the same privileges.

We hope that you’ll join Ruth and reach out across the globe to give the gift of education to impoverished girls and women in Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Pakistan

By Sonja Bahr

Central Asia Institute depends on the commitment and generosity of supporters like you to unlock the potential of girls and women through education. Many of our supporters want to ensure future generations of children in Central Asia receive the gift of education but aren’t sure how to go about it.

Here are just a few of the ways your commitment today can provide hope and opportunity for current and future generations, while also providing benefits such as tax deductions and regular income for life for you and your family.

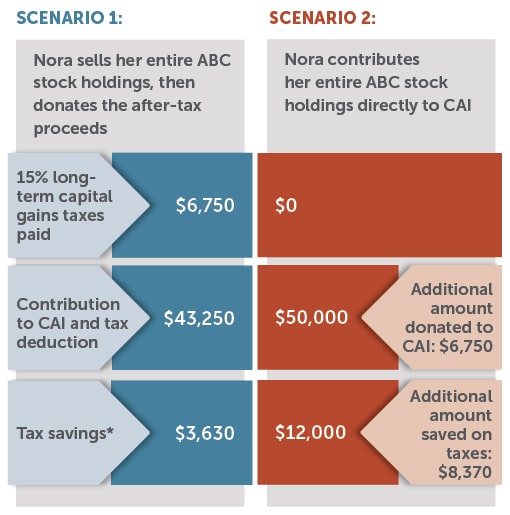

Donating appreciated stock is an excellent option for donors who would like CAI to benefit from gains made in the stock market while reducing their tax liability. A donation of stock is an easy transaction, and donating appreciated stock held at least one year typically avoids capital gains tax for the donor.

Here’s a scenario that demonstrates this: Nora purchased 1,000 shares of ABC 10 years ago at $5 per share. ABC stock is now valued at $50 per share, making Nora’s holdings valued at $50,000. If Nora donates the stock directly to CAI, three things happen: she can deduct her gift from her taxes; she can avoid paying capital gains tax on the $45,000 earnings on the stock; and she is able to increase the size of her gift to CAI while lowering her overall tax bill.