Sitora Majnunova, 41, lives with her brother and daughter in the Roshkala district in Tajikistan’s marginalized Gorno Badakhshan region. Following the death of her husband a few years back, Sitora was at an all-time low. Although she had a passion for sewing, she lost interest in life. She explains, “I had stress and was sick after my husband’s death and nobody could encourage me.”

But all that changed when she decided to attend a CAI-supported training on financial literacy organized by CAI-Tajikistan. Sitora remarked, “It was transformative. The pieces finally came together, and the group of women were so supportive and nurturing.”

“I’m so amazed that my attitude towards life could be changed in such a short period, and allow me to start a business, make a profit. The training motivated me to improve my life and my daughter’s. With the knowledge I gained, I prepared a family budget plan including sources of regular and non-regular income, expenses, and how to save.”

Now Sitora has converted her passion into a business creating traditional Tajik garments including woolen carpets for wedding ceremonies, skull-caps for girls, and woolen socks.

The training provided the launching pad for Sitora’s business to take off, and she hasn’t

slowed down since. She has continued to evaluate her business, study the market for her goods, and develop new and creative ideas.

“I am thinking of new business ideas and doing research on product demand in the market.”

Sadia Sahar, 24, lives with her large family in the Khash District in Badakhshan. Her parents are farmers. While Sadia was lucky to attain a bachelor’s level education, she worried about her ability to work, especially under Taliban rule.

“We are a family of ten and I am the eldest. I completed my studies, but previously had no opportunity to find a job in our area to help support my family. Of course, the income from farming is insufficient for our needs.”

She graduated with a degree in Chemistry from Badakhshan University in 2019 but felt devastated when, after two years, she could not find a job.

Following the Taliban takeover in August 2021, the environment for women completely changed in Afghanistan. Sadia remembers feeling utter distress. But, like so many other women in Afghanistan, she had no choice but to keep striving towards her goals.

“I was disappointed but kept busy helping my mother with household chores, farm work, and livestock.”

When she learned of the opportunity to work as a teacher at a community-based school established by CAI, she jumped on it.

In addition to earning an income, she feels her social status has been enhanced, and the trainings have improved her qualifications academically. She has received training in pedagogy, psychology, teaching methodology, and child protection measures.

Now Sadia has a clear vision for her future; she is helping to support her family and saving money to pursue her Master’s Degree. Sadia is not giving up on her future, and neither is Central Asia Institute.

“I am paid $100 per month and spend some on my family and save some money to start my master’s degree when I have saved enough.”

For the teachers of Central Asia Institute’s Afghan Girls Education (AGE) program, environmental stewardship and education go hand in hand. This spring, classrooms in four Badakhshan districts launched a new initiative to plant one tree for every student in class. Their goal: to make Afghanistan green.

Mrs. Bashira, a teacher from Dehqan Khana, was thrilled to take part in the “One student, one tree” campaign. She and her students planted five trees in their classroom area, sparking joyful reactions from the children.

Marjan, one of Mrs. Bashira’s students, was excited to be a part of the campaign and said that it was the first time she had ever planted a tree. For her and her classmates, it was a unique experience and has become a source of pride as they tend to the young trees.

The campaign similarly received a warm welcome from the surrounding communities. Mr. Namaz, a teacher from Kata Dara reflected: “Children are like newly planted trees. They require nurturing, attention, and care. It is crucial for families and parents to take responsibility for their children’s education and growth. Only then can we hope to achieve a green and prosperous Afghanistan.”

With more than a third of Afghanistan’s forests lost in the past three decades, there is a long journey ahead to bring back the greenery. However, education about climate change and the conservation of natural resources is one important piece of the puzzle. These teachers and students are helping lead the way to a greener Afghanistan.

Barushan is a small town nestled in the Pamir Mountains in Tajikistan’s Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Oblast (GBAO) region. A poor and isolated province, GBAO grapples with neglected infrastructure and limited economic opportunity. Many of the schools in the region have not been renovated for decades, putting children and teachers at risk of building-related illness and injury. Despite the perilous conditions, families have remained steadfast in their commitment to education.

Since its establishment in 1962, Preschool #2 has been the only preschool in Barushan, serving the 3 to 5-year-olds of the community. Even with sagging ceilings, mold, and smoke-stained walls from coal-burning stoves used for heat, there was a waitlist to get in. That’s when you stepped in to help.

Fresh on the heels of constructing and opening a model school in Udit village in 2019, Central Asia Institute broke ground on Preschool #2. Although the work is now in its final stretch, the path has not been easy since construction began in 2021. Supply chain limitations of the Covid era exacerbated the existing challenges of high mountains, dangerous roads, and harsh winter weather.

The completed school will contain five classrooms, a kitchen, a nurse’s office, and art and music rooms. It will have central heating, indoor latrines, piped water, and electric power.

During 2021 and 2022, construction crews laid a strong foundation for the two-story building that will serve 125 3 to 5-year-olds. Spring of 2023 has seen progress on completion of the second story as well as interior plastering, heating, and eletrical work. Throughout the summer and early fall, the building will continue its transformation into a safe and high-quality educational environment for Barushan’s youngest learners.

The impact of Preschool #2 will be monumental for the 125 preschoolers, their families, and teachers—and it won’t stop with them. As a model school for the region, the school will be home to training workshops for teachers and administrators and serve as an example for future projects in the area. With a built-to-last design and materials, the school will serve these 125 preschoolers along with hundreds more in the years to come.

Support from the friends of Central Asia Institute has made this work possible—and there is still time to help this project get to the finish line. Please consider a gift to Preschool #2 today.

Defiant Dreams

By Sola Mahfouz and Malaina Kapoor, 2023

Mahfouz and Kapoor shed light on the experiences of everyday Afghan girls and women through Sola Mahfouz’s incredible story. Born at the start of the Taliban’s first reign, she was unable to add or subtract at the age of 16. Through sheer will and grit, Sola educated herself and went on to become a quantum computer researcher in the United States.

Azan on the Moon: Entangling Modernity Along Tajikistan’s Pamir Highway

By Till Mostowlansky, 2017

Mostowlansky offers an in-depth, anthropological study of people’s lives along the Pamir Highway

in eastern Tajikistan, a road that profoundly changed the material and social fabric of a former Soviet outpost on the border with Afghanistan and China.

Postcards From Stanland: Journeys in Central Asia

By David H. Mould, 2016

Postcards From Stanland provides a glimpse of the people, landscapes, and customs of some of the diverse countries of Central Asia—Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan—and paints a rich picture of this post-Soviet world.

I Am Malala: The Girl Who Stood Up for Education and Was Shot by the Taliban

By Malala Yousafzai, with Christina Lamb, 2015

I Am Malala is the story of a 15-year-old Pakistani girl who fought for her right to an education and was shot in the head by the Taliban while riding the bus home from school. Malala survived and became a symbol of peaceful protest and a Nobel Peace Prize recipient.

Half the Sky: Turning Oppression Into Opportunity for Women Worldwide

By Nicholas D. Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn, 2010

Kristof and WuDunn introduce readers to women and girls in the developing world who are struggling against oppression and then show how, with only a small amount of help, their lives are transformed and potential is unleashed.

America and the Taliban, PBS Frontline

Martin Smith, 2023

Drawing on decades of on-the-ground reporting and interviews with Taliban and U.S. officials, this epic three-part investigation traces how America’s 20-year investment in Afghanistan culminated in a Taliban victory and examines the missteps and consequences.

Bread and Roses

Sahra Mani, 2023

This feature film captures the harrowing and heartbreaking experiences of Afghan women in Kabul after the Taliban retook control of Afghanistan. It premiered at Cannes Film Festival and

is not yet available for streaming.

SOLA: Daring to Educate Afghanistan’s Girls, CBS 60 Minutes

Lesley Stahl, 2023

This 60 Minutes piece follows a group of Afghan girls who fled their country after the Taliban regained power and settled in Kigali, Rwanda, where they are attending the School of Leadership Afghanistan (SOLA) and getting the education they crave. Available for streaming on CBS.

Frame by Frame

Alexandria Bombach and Mo Scarpelli, 2015

Frame by Frame chronicles the plight of four Afghan photojournalists as they work to build a free press after decades of war and oppression during the Taliban regime. Available on Apple TV.

Kabul Falling

Project Brazen, in partnership with PRX, 2022

On August 15, 2021, the Taliban regained control of Kabul nearly 20 years after coalition forces had cast them out of power. In this riveting podcast, you’ll hear first-hand accounts from Afghans who attempted to flee their country in the final days of the U.S. withdrawal and learn of their struggles to rebuild their lives at home and abroad.

The New Afghanistan, Through the Eyes of Three Women

Christina Goldbaum, The Daily, New York Times, 2023

This episode of The Daily profiles three Afghan women who are coping with the Taliban’s return

to power and the new restrictions on women and girls.

Whether you choose to give a direct monetary donation, a gift of stock, or an in-kind gift, CAI appreciates your support. And we’re excited to tell you about a few new, easy ways to donate.

Thousands of companies will match donations made by their team members, retirees, and even employees’ spouses. Find out if your employer will double or even triple your donation to CAI with a quick search of Double the Donation’s online database, which allows you to access your employer’s matching gift forms and complete the simple, minutes-long process to drive additional support toward our cause.

Recently, CAI became eligible to accept vehicle donations by partnering with CARS, a California-based 501(c)(3) nonprofit social enterprise that only supports other nonprofits in their fundraising efforts.

Do you have an old car you no longer drive that’s just taking up space in your garage? Or maybe you have a motorcycle that stopped working years ago that you never got around to fixing. Consider donating it to CAI!

All vehicles are considered! CARS strives to accept all types of donated vehicles (running or not) including cars, trucks, trailers, boats, RVs, motorcycles, campers, off-road vehicles, planes, heavy equipment, farm machinery, and most other motorized vehicles.

To find out if CAI can accept your vehicle, please complete the secure vehicle donation form on our cars website: careasy.org/nonprofit/central-asia-institute

Or call CARS directly at 855-500-7433 during regular hours of operation:

By Nicolas Pavoncelli

Over the past year, Central Asia Institute has been working closely with our partners on the ground to understand how the changing climate is impacting the children, families, and communities we serve, and using education to empower them to mobilize and adapt.

The year 2023 is already on track to be one of the hottest years on record. Across the globe, people are feeling the effects of rising temperatures and witnessing more severe, climate-related flooding, droughts, and heatwaves. While these changes impact developed and developing countries alike, it is the world’s poorest and most vulnerable populations, especially women and children, who are the most affected and the least equipped to react.

Over the past year, CAI has been working closely with our partners on the ground to understand how the changing climate is affecting the children, families, and communities we serve, and using education to empower them to mobilize and adapt.

The Hindu Kush, Karakoram, Pamir, and Himalaya mountain ranges are part of a complex system situated at the center of Asia, traversing the borders of China, India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan. They comprise the greatest concentration of high mountains in the world, and their glaciers are the water source for more than a billion people. The inhabitants of this region are often largely isolated from the rest of the world, yet they are not immune from the impacts of a changing climate system.

Warmer temperatures, receding glaciers, and increasingly low levels of annual rainfall are affecting their agricultural output and food security. More frequent avalanches and more severe springtime flooding leave people without power, access to roads, and emergency services for months at a time. Unfortunately, the limited capacity of local and national government authorities to prepare for and respond to the effects of climate change, combined with fragile infrastructure and inadequate social safety nets, exacerbates these critical vulnerabilities.

These problems are already playing out in the areas of Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan where Central Asia Institute has long worked. In 2022, unprecedented flooding in Pakistan caused 1,700 deaths, impacted 15% of the population, and critically disrupted the lives and education of 2.3 million school-aged children.1 Afghanistan has been experiencing a prolonged and severe drought since 2018. In that year alone, the severe lack of rainfall displaced a quarter of a million people. And last year, a massive avalanche in Khorog, the capital of Tajikistan’s Gorno-Badakhshan region where CAI works, left 17 people dead.

The remote and impoverished communities of Central Asia contribute little to global warming, but they suffer more because they lack the resources and government services needed to cope. Most are without air conditioning when temperatures soar during the summer months and without proper heating and insulation during the harsh winters, when temperatures can plummet to -20°F. They often lack access to safe drinking water, and drought conditions undermine their food supply and main source of income.

Photo by Sa’adia Khan

Even within vulnerable communities, the harm caused by severe weather and climate-related disasters is not felt equally. Evidence shows that women and girls are disproportionately affected. According to research conducted by the UN Development Programme, four out of five people displaced by weather-related disasters like floods and droughts are women, mainly young girls.2 In places like Afghanistan, poor families struggling to cope in the wake of disasters are more likely to marry off their daughters—sometimes as young as 13—to reduce the financial burden on their already impoverished households. In addition, household chores that primarily fall to women and girls, such as fetching water, are becoming more challenging and time-consuming during episodes of drought, preventing young girls from attending school or completing their homework. The Malala Fund estimates that due to these and other factors, 12.5 million girls will be denied access to education by 2025.3

For Central Asia Institute, an organization dedicated to advancing female education, combatting climate change could not be more vital to our mission. As CAI Executive Director Alice Thomas explained, “While women and girls are being disproportionately impacted by climate change, they are also key to ensuring that their families and communities can effectively prepare for and adapt to its effects. For CAI and our partners, empowering them with relevant knowledge and information is critical.”

In 2023, CAI began collaborating with our local partners to explore potential projects and activities to help integrate climate education into our programs. We received overwhelming support from our partners, as well as teachers and schools across the communities we serve. And while these projects are just getting off the ground, the results so far are inspiring.

In Afghanistan, for example, environmental education is being incorporated into teacher and community leader (shura) training. One of CAI’s partners, Shining Star Education Organization of Afghanistan, has created a climate change booklet for teachers and students. And tree planting, a proven strategy for reducing flooding, landslides, and soil erosion, has proven a fun and effective way to engage the entire community and empower them to play a role in addressing the adverse effects of climate change.

Students watering a recently planted tree, Khaki Jabar, Afghanistan.

In Pakistan, CAI’s partner hosted an Environment Day, which kicked off with a quiz of students’ climate knowledge, followed by a lecture to educate students on the importance of environmental awareness. Our Pakistan partner is also collaborating with other nonprofits, notably WWF-Pakistan,4 to spread climate change awareness, conduct environmental education with teachers and students, and discuss sustainable livelihoods.

These inspiring programs, along with our deepened understanding of how climate-related impacts are affecting the areas we serve, have strengthened our resolve to incorporate climate change into our mission of transforming lives and communities through education. We look forward to keeping you updated on these innovative programs. With our partners and your support, we hope to not only make a difference in the lives of those who are most vulnerable, but also to empower them to protect their local environment and way

of life.

1UN OCHA Pakistan, https://www.unocha.org/pakistan

2UNDP (2016) Policy brief: Gender and Climate Change.

3A Greener Fairer Future, The Malala Fund

4 ® “WWF” is a WWF Registered Trademark

By Libby Daghlian

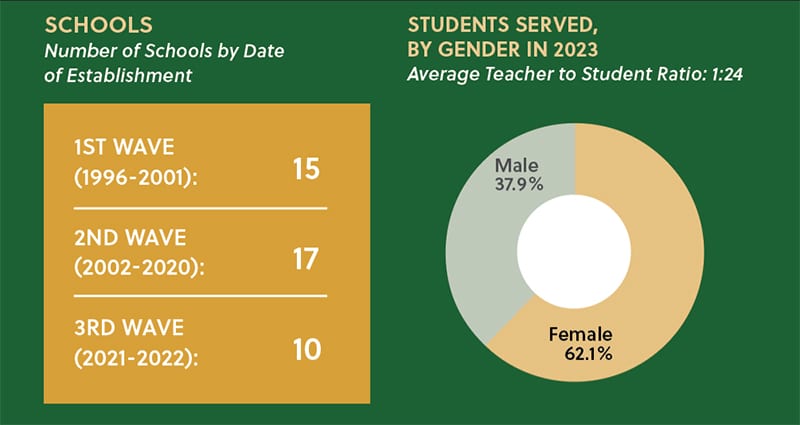

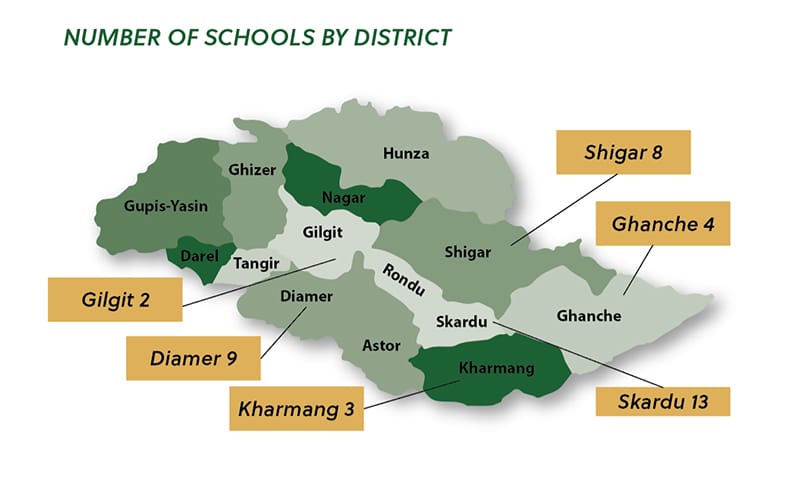

Central Asia Institute’s story begins in 1996 in the mountainous region of Gilgit-Baltistan in northern Pakistan. Today, CAI continues to support 42 schools spread out across six districts and situated among soaring peaks. These schools are full of incredible stories, like the students who grew up to be teachers in the schools they attended as children, and the community members who rallied to help with repairs or donated their time to school councils. Take a journey with us across time and space to see what these schools have achieved, and what is still on their horizon.

CAI currently supports 42 schools in Pakistan serving 6,231 students. In five out of six districts, the number of female students is higher than the number of male students. There are 269 teachers working in these schools—102 are female and 167 are male. One of CAI’s priorities is to increase the number of female teachers.

Over time, the demand for education in these communities has grown. Girls in Pakistan have faced greater barriers to education than boys, particularly in poor, rural areas, thus the emphasis on increasing enrollment for girls in CAI schools. Today, the most common need across the schools is for additional classroom space, not only to ease overcrowding but also to allow these schools to serve more grade levels. With several schools providing education for girls only to eighth grade—as opposed to tenth grade for boys—many girls are unable to continue their education, since attending attending high school in faraway towns or cities is not an option.

At the other end of the education spectrum, preschool classes for children aged 3 to 5 are also high on the list of needs. At present, only half of the schools have the facilities and teachers required to make early childhood development possible for these young minds to thrive in school and later in life.School renovations, upgrades, and repairs are also greatly needed. Schools established in CAI’s early years (1996-2001) are more likely to require improved drinking water systems and gender-segregated toilets, which both promote good health and hygiene and incentivize older girls to stay in school. Those schools established more recently (2021-2022) need more teachers to fill the unmet demand for education in these areas.

Looking ahead, Central Asia Institute is focused on a continuous improvement approach for schools that requires regularly tracking and verifying needs and progress. In addition to meeting needs identified by the schools, CAI is working towards higher retention rates among upper-level female students and an increase in early childhood education participation. Our goal is to ensure these schools continue not only to be a source of pride for these communities, but also to play a critical role in making education—especially for girls—possible in these remote and underserved mountain areas.

CAI Board member Mina Sherzoy has never been one to shy away from a challenge. From empowering Afghan women to pursuing a career in fashion design to raising two daughters as a single parent, she has no shortage of impressive accomplishments.

Growing up in Afghanistan during the late 1960s and 1970s, Mina’s family supported her as she pursued her education and her dreams. While she acknowledges it was a “male-dominated culture,” it was nothing like what it is today under strict Taliban rule. “My parents were always for education, development, and personal growth. They always encouraged me to study, to be the best,” she said.

During the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, Mina was forced to flee at the age of 17. At the time, her father was an ambassador in Prague. “It’s funny because I used to travel through communist countries and would feel sorry for them because it was so hard to live there,” she said. “But I didn’t know that one day it would happen to us.” Her family reunited and fled together to the United States, eventually making their way to California. Soon after arriving, Mina got married, had two daughters, and navigated life in a new country. “I was young, scared, and had lost everything—all the dreams, hopes, identity. When you become a refugee, the first thing you lose is your identity—who you are.” Although she had always planned to go to university, the demands of family and work presented tremendous obstacles. “This is where I lost track of my education. I had to work, I had to raise two kids, and ended up in an unhappy marriage. But still, in the back of my mind, I told myself that one day I will go to university and get that bachelor’s degree, no matter what.” Eventually, she did.

Mina enrolled at the University of Phoenix, having to balance work, parenting, and her education all at once. “I struggled to get that degree!” The experiences she had during those years ended up being some of the most formative of her life, and she wanted to share what she learned with her fellow Afghans.

She finally got the opportunity to go back to Afghanistan after 9/11 and the U.S. invasion, when there was a wave of positive social change, especially for girls and women. Mina was determined to go back to her home country and be part of it. “When I went back to Afghanistan, I reconnected with people who had remained during war. I told them what I had gone through and I was encouraging their kids not to miss all the opportunities that the international community had brought in—the scholarships, the free education. Everybody wanted to get educated, but they needed to know where to go and what to do. All they needed was guidance. You train them, you equip them, and then let them fly like a bird. And this is how I came to work back in Afghanistan.”

I want to do this work for the next generations: The Americans who are in international development, not to be the way they were in Afghanistan. And for the next generation of Afghans, to learn not to believe everyone’s promises and to be self-sufficient and collaborative.

While in Afghanistan, Mina founded the Afghan Women Business Association and Afghan Women Business Federation. She also worked with USAID to launch Afghanistan’s first female private-sector business federation and participated as an observer in the Afghanistan Independent Election Commission.

In 2004, Mina met a young woman who had come to Kabul from the provinces and wanted to be a doctor. Mina was able to connect the woman with a scholarship to study medicine in Romania, but her family wouldn’t allow her to go. Curious as to their reasoning, Mina went to meet with the woman’s father and her brother, who was, himself, a medical doctor. She was shocked by what she heard. They believed that if the young woman traveled abroad, she would become a prostitute. Looking the brother in the eyes, Mina said, “You have studied, but you haven’t grown.”

Mina hired the young woman to work on her USAID project. As soon as she began earning an income, her status in the family changed completely. One day, the woman told Mina, “You know, they respect me at home. Now I don’t have to wash the dishes or care for my younger siblings. When I come home, my food is ready.”

Throughout her work in Afghanistan and the surrounding countries, Mina gained profound insights into the challenges of development in the region where she grew up.

“South Asian women face common challenges in a male-dominated society. They all face a lack of social support and lack of political support. There is violence, nepotism, and corruption. I kept thinking that half of the population in that South Asian belt is paralyzed. And then you sit here in the Western world and say, ‘Why is there insecurity? Why are there terrorists? Why is there drug dealing? Why is there human trafficking?’ When half of the population is paralyzed, what other outcomes do you expect?”

Mina sees her work as critical to changing things in both America and Afghanistan. Although the return of the Taliban in 2021 made Mina a refugee for the second time in her life, she continues her work with refugees by supporting resettlement agencies as Afghans navigate their new realities in the United States. “I want to do this work for the next generations: The Americans who are in international development, not to be the way they were in Afghanistan or any other developing country. And for the next generation of Afghans, it is imperative to grasp the lesson of not placing blind trust in every promise made and to be self-sufficient and collaborative.”

For Mina, serving on the Central Asia Institute Board helps to fulfill her desire to continue giving back and sharing her tremendous expertise and lived experiences. “Everyone is so passionate about this cause. What I like about Central Asia Institute, it’s not just about Afghanistan. It’s Pakistan, Tajikistan, too. CAI has come a long way. Everybody is doing this work from their hearts.”

Are you interested in getting more involved with Central Asia Institute?

Do you have experience serving on nonprofit boards or in international development, nonprofit management, or fundraising?

Drop us a note at info@centralasiainstitute.org.

We’d love to hear from you!

Mina is a Program Officer with the US Committee for Refugees and Immigrants. She founded Excel consulting and has held key leadership roles in international development projects, including USAID’s Director of Business Association Development for Trade Show Support Activities and Director for the $40 million USAID Promote Women in Government (WIG) program, the largest women’s empowerment project in the world.

By Libby Daghlian

For more than 20 years, Central Asia Institute has supported students in Tajikistan with scholarships to continue their higher education studies. Falling under the pillar of accessibility, scholarships bridge a critical gap for Tajikistan’s young adults. While literacy rates in the country are high and many students graduate high school, the choice to continue to university is not an easy one. The cost can be prohibitive, and high unemployment rates leave prospective students fearful about the return on investment.

For professionals like Afsona Gulzorova, access to higher education was an invaluable part of her journey toward building a strong foundation for her career and family. With a scholarship from Central Asia Institute, Afsona was able to earn a bachelor’s degree in history from Khorog State University in 2020.

After graduating straight into a global pandemic as a young mother, Afsona had to practice Zen-like patience in landing her first job. But it all paid off in 2022, when she started the rewarding role of teaching history to sixth- and seventh-grade students at School #5 located in Khorog, the capital of Tajikistan’s Gorno Badakhshan region. Recently, Afsona accepted a new job with the local government and is thrilled to continue building her professional experience and achieving her financial goals.

“I always share my experience with my students and friends,” explained Afsona. “To me, an education is a light that guides you towards a better life.” For Afsona, the alternative was all too clear. Growing up, her parents earned very little but instilled in her a passion for learning and a belief that she could achieve her goals. As she neared high school graduation, she saw many friends leave Tajikistan for other countries, primarily Russia, in search of better employment prospects.

Without a scholarship, Afsona would have had no choice but to follow suit and look for work in Russia. Identifying and winning a scholarship was the catalyst Afsona needed to remain in her home community and be a part of building a brighter future there. The ripple effect of her scholarship extended to her parents, allowing them to focus on building their own financial security as well. “The fees that CAI paid during my studies took the burden off my parents. Otherwise, they would have had to borrow on credit and would have really struggled to pay it back.”

As Afsona demonstrates, a scholarship for one student becomes a beacon of light for a whole community. Central Asia Institute’s investment in Afsona gave her the gift of higher education, which spread to her family, her school, and her community.

“As a mother, I am happy I pursued higher education. Everything that I learned during university continues to help me in my daily life,” said Afsona.

Multiplied across many students and consistently applied throughout decades, these scholarships can have a transformative effect. In a place like Tajikistan’s Gorno-Badakhshan region, isolated from economic opportunities, it is especially important to support students and families through challenging economic times.

Tajikistan is unique in that older generations are, on average, more educated and have completed higher levels of education—often at the graduate level—than younger generations. That is because unlike when Tajikistan was part of the Soviet Union, the current government is unable to provide adequate social safety nets and access to advanced education and professional degrees. In recent decades, the country has struggled economically and the lack of jobs and the departure of young people to other countries has threatened this track record of highly educated communities. At Central Asia Institute, we are hoping to counter that trend, knowing that when educated and ambitious young people are empowered to remain in their hometowns, the whole community benefits.

We could not be prouder of Afsona and all of our scholarship recipients in Tajikistan!

By Libby Daghlian

Nestled in the breathtaking mountains of Pakistan’s Gilgit-Baltistan region, the city of Dain is home to a thoughtful young preschooler named Moheed.

Coming from a modest home, Moheed spent the first years of his life close to his mother Zaheera, observing her daily routines and responsibilities, and testing the limits of his quickly developing skills. Although this time together was precious, Zaheera was determined to give Moheed a strong start to his education, which meant searching for an early childhood center (preschool) in which he could enroll.

In Gilgit-Baltistan, like many parts of the world, early childhood education and care is in short supply. Despite strong evidence of the benefits of early learning and development opportunities, preschool remains underfunded and undervalued compared to other stages of the educational journey. While there is a great deal that parents and caregivers can do to support this period of rapid cognitive and physical development, balancing these demands with work, maintaining the home, and other caring responsibilities makes it challenging.

The fertility rate in Gilgit-Baltistan is 4.6 children per woman, so parents and families must manage the care of multiple children at many different stages of development. The data show the precarious nature of this situation. According to a 2017 report from UNICEF1, more than 27% of Gilgit-Baltistan children aged 3 to 5 had been left in the care of another child under the age of 10 in the past week. The same report showed that close to 40% of children aged 3 to 5 in the region were not on track in at least four major developmental categories, including literacy-numeracy, physical, social-emotional, and learning.

Further investigation revealed that families lacked many of the basic resources needed to supply an enriching learning environment at home. Only 6% of children 3 to 5 years old had access to three or more books at home, and only 31% reported having a caregiver engage the child in a learning activity in the prior week. Looking at fathers’ involvement in learning activities specifically, the rate was abysmal, at just 2%.

Zaheera knew what she was up against, but also had a clear vision for her son’s educational journey. Although she did not have the opportunity to attend preschool herself as a child, she had taken the time to learn about its benefits. It was both validating and delightful to see these benefits come to life when Moheed started at his new school.

“I took a leap of faith and enrolled my son in the Early Childhood Development Center, Dain,” said Zaheera. “Within a remarkably short period, I observed positive changes in my son’s behavior. He has started to develop good habits, such as organizing his belongings, greeting others with respect, brushing his teeth regularly, and neatly folding his clothes.”

Early childhood education has the potential to be transformative for communities. Not only can these programs improve school readiness among children and boost social-emotional skills, they also have the potential to close social mobility and achievement gaps. In very low-income communities where families may already be strapped for time and resources, these interventions are critical for community development and supporting a new generation of engaged and capable leaders, workers, and families.

The impact is not only borne out in study after study from different parts of the world but also demonstrated in the demand among families.2 Parents and caregivers like Zaheera benefit from high-quality early childhood education both in terms of their child’s development and their ability to invest in other areas such as work, homemaking, community involvement, and respite from the demands of caring for small children.

Teachers like Muhammad Tahir are invaluable in not only providing quality education to these children but also in their efforts to change attitudes in their communities. In a small town in the Diamer Valley, Muhammad has had to navigate conservative beliefs about girls’ education, gently changing minds along the way.

With no other schools nearby, Muhammad had to forge his own way. With the help of CAI and our local partner, the Moawin Foundation, he was able to identify a building to house his small school. Starting with just a few students, demand for Muhammad’s school quickly grew as parents saw the positive impact on local children. “Chilas is a conservative area, where parents were initially hesitant to send their daughters to school,” he said. “As they observed my efforts and the impact on children, they started sending more girls to the school. I am hopeful that this school will make a significant impact on the lives of children in the community.”

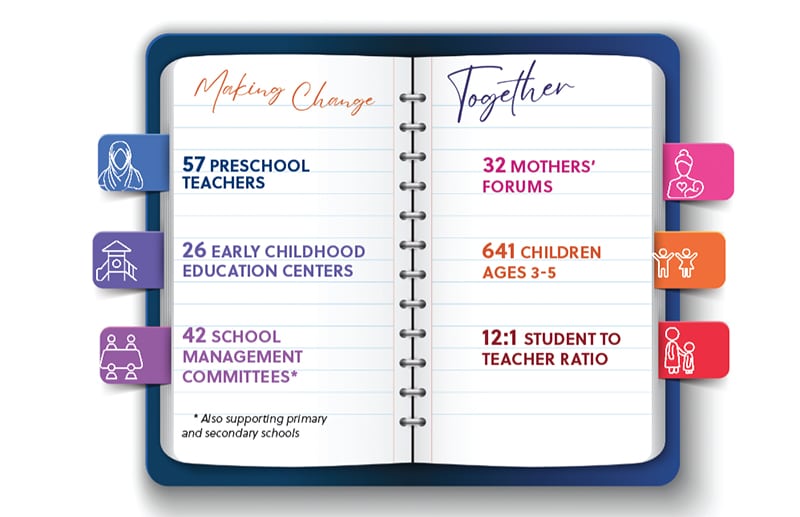

Muhammad is one of 695 teachers supported and trained by Central Asia Institute. Of these, 57 are specifically trained in early childhood education. For CAI, the commitment to early childhood education grew out of attention to educational research, as well as the demand of our communities.

Working hand in hand with our local partner and community leaders, CAI has increased investment in early childhood education in Pakistan through the establishment of new centers, training and hiring new teachers, and finding creative ways to keep families and parents engaged.

Throughout 2023, Central Asia Institute has expanded our early childhood education footprint through the addition of 10 new centers, bringing the total to 26 preschools that serve 641 children. Fifty-seven teachers have been trained in child development, kindergarten readiness, and Montessori methods, providing an important complement to their formal training. But the investment does not stop with the school.

To provide comprehensive and thoughtful support to the children and their families, “Mothers’ Forums” have been established at 32 schools. In a cultural context where women are often discouraged from seeking leadership positions, these forums provide an empowering space for women to become true advocates for their children. In the words of our local partner, the Moawin Foundation, the forums are “powerful platforms for empowering mothers and nurturing a culture of active participation in their children’s education journey.”

In a place like Gilgit-Baltistan, the challenges are intense. The poor economic context combined with a high prevalence of child labor, domestic violence, and early marriage put children in a particularly vulnerable position. Yet, the very communities grappling with these pain points are also a source of tremendous hope.

Women are leading the charge toward a brighter future. More and more women and girls are standing up for their rights and paving the way for gender equity and education in their region. Zaheera is enthusiastic about her role in this change. She knows that her decisions for Moheed are part of building a new generation of educated citizens and leaders. And Central Asia Institute is proud to stand by her side.

1Planning & Development Department, Government of the Gilgit-Baltistan and UNICEF Pakistan. 2017. GB Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey, 2016-17, F report. Gilgit, Pakistan: P&D Department, Government of the Gilgit-Baltistan and UNICEF Pakistan.

2Isaacs J and Roessel E. 2008. Impacts of Early Childhood Programs. Brookings.

By Libby Daghlian

Imagine the start of a perfect school day. You might envision the faces of smiling children waving goodbye to their parents. There might be a bell ringing and open doors to a sturdy and welcoming brick building. Inside, the walls and floors would be smooth and clean, and the temperature would be just right. The classrooms would be bright and cheery, and the students would have space to sit comfortably and store their belongings. On this perfect school day, students and teachers alike would have a clean, private bathroom space to use and water that is safe for washing hands and refilling water bottles. In this kind of environment, teachers feel confident in welcoming their students, and children feel safe and ready to learn.

Unfortunately, in Tajikistan, many school buildings have gone decades without renovation or regular maintenance and they are not only uncomfortable but unsafe. The impact of these conditions extends to long-term educational outcomes. According to a 2019 Word Bank report,1 inadequate water, sanitation, and hygiene facilities at schools were directly tied to student absenteeism and dropout rates, especially as adolescent girls deal with the additional task of managing menstruation.

For more than two decades, Central Asia Institute has built and renovated school buildings across the Gorno-Badakhshan region of Tajikistan, providing children with modern, safe educational facilities where they can learn and thrive.

In 2024, Central Asia Institute will open the newly constructed Preschool #2, which was supported by generous and caring donors like you. Preschools are critical to early childhood development and can contribute to a child’s success, not only in primary school but later in life as well.

My name is Amira. I am 5 years old. The new school will be red. There will be lots of lamps there. Our old school was broken. There wasn’t a place for games. The new preschool will have slides, stairs, toys, and a playground.

We spoke to some of the teachers and students who are part of the Preschool #2 community to learn what the new school means to them.

Retired teacher Shogunbekov Amrikhudo recalls when the original Preschool #2 building was erected. “The construction of the old building started in 1960 and was opened in 1964. I was a fourth-grade student at that time. After several years, the building slowly started to deteriorate.”

Shogunbekov is excited that the community will finally have a new school after 60 years. “In the future, the kids will live and study in very good and modern conditions, learn languages, and become good specialists that could create a better world for the people of this country.”

Maqbulova Gashnis, a longtime teacher at Preschool #2, has experienced firsthand just how difficult and frightening it can be to work in a building that has not been well maintained. “Our school building was in a state of disrepair. During the earthquake of 2016, we were very scared because the earthquake was strong, and we took all the children and ran out. We still keep that fear in our hearts.”

My name is Soro and I am 5 years old. I like playing with toys and dolls. In the old preschool, there was wind, and we went to the toilet in the snow. The new preschool will have a place for eating and playing. It will be beautiful.

Shogunbekov is excited that the community will finally have a new school after 60 years. “In the future, the kids will live and study in very good and modern conditions, learn languages, and become good specialists that could create a better world for the people of this country.”

Maqbulova Gashnis, a longtime teacher at Preschool #2, has experienced firsthand just how difficult and frightening it can be to work in a building that has not been well maintained. “Our school building was in a state of disrepair. During the earthquake of 2016, we were very scared because the earthquake was strong, and we took all the children and ran out. We still keep that fear in our hearts.”

She also cites the challenges with properly heating an old building, which is crucial during the cold winter months high in Tajikistan’s mountains. “We have very challenging winters. Since it is very cold, we have to burn coal, which makes smoke in the classrooms, and that smoke is certainly harmful for children.”

Maqbulova is optimistic about the new building: “When I imagine a new building, it is spacious, clean, and warm, with nice windows, no coal smoke or dust. We don’t have to worry about heating anymore. Our hands are clean, and our children are neat and tidy.” She says the children are equally curious and eager for the grand opening. “When we come to work in the morning, the children ask us: What will happen in the new preschool? Everything will be new? New toys, new books, new beds? When we go out, will there be a playground?” With amusement at their curiosity, she assures the students daily that yes, it will all be new.

1 “The Impact of School Infrastructure on Learning.” The World Bank. 2019. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/853821543501252792/pdf/132579-PUB-Impact-of-School.pdf#:~:text=The%20potential%20benefits%20of%

20improving%20the%20spaces%20where,enhanced%20in%

20schools%20with%20better%20physical%20learning%20environments.

Shortly after seizing power on August 15, 2021, the Taliban announced, “We are going to allow women to study and work within our framework. Women are going to be very active in our society.”1 But over the following two years, they failed to deliver on this and numerous other promises. In fact, they proactively instituted a set of inhuman edicts to achieve the opposite—a society in which women are brutally forbidden to participate, study, and work.

While the Taliban acted with boldness and impunity, we must not assume the people were complacent or accepted these new policies. Afghanistan is a complex and diverse country, and opinions about women’s role in society vastly differ between cities and rural areas; between the country’s north, where CAI implements most of its programs, and its south, which is the Taliban’s power center; and even within communities and families.

As Central Asia Institute and our partners on the ground continue to navigate the new environment under Taliban rule, we’ve seen this struggle play out. Yes, the Taliban’s bans on secondary education for girls and university for women have forced us to narrow the scope of our programs, predominantly to focus on primary school. But we’ve also found a huge demand for our community-based classes—including for girls—in areas where there are no schools and where many adults have little to no education. And in several instances in which the Taliban sought to interfere with these classes, it was the communities themselves that fought back. Today’s Afghans are not the same as they were 20 years ago. In cities and rural areas alike, most highly value education as the best chance for a better life. Despite the challenging operating environment, we’ve continued to deliver education programs to girls, including in remote, rural areas that are culturally conservative.

The timeline below presents a snapshot of events that reflect both the Taliban’s campaign to strip Afghan women and girls of their rights to education, work, and freedom of movement, as well as big and small ways Afghans are fighting back.

Taliban fighters take control of Kabul as Afghan government officials flee amid a chaotic and deadly withdrawal and evacuation effort by U.S. forces.

Despite assurances that all schools would reopen for the new academic year, girls returning to secondary school are ordered to go home, and their schools are closed until further notice.

Women in Kabul are banned from public parks, gyms, swimming pools, and public baths, leaving them nowhere to recreate or take their children to play.

Women are banned from attending university.

Female students protest outside Kabul University as their male counterparts return to classes. 5

Afghan women increasingly take their protests indoors and online, posting pictures and videos on social media to keep the world focused on their plight and allow human rights organizations to document Taliban abuses. 7

By Molly Shapiro

When the United States withdrew from Afghanistan in August 2021 and the Taliban took over, one of the biggest questions was whether women and girls would lose their hard-fought rights—from freedom of movement to education to career opportunities. Tragically, that question was answered quickly, when the Taliban began issuing a rapid succession of severe edicts that drove women from the workplace, forbid them from education beyond the sixth grade, and banned them from all aspects of public life.

In a little over a year, women had lost almost everything they had gained during the two decades without Taliban rule. No more high school or university. No hope for a job to make money or a meaningful career. No opportunity to go to the gym, a park, a swimming pool, or a public bath. The one thing that remained—the chance to gather and socialize at the beauty parlor—was taken away in July 2023.

Not surprisingly, this desperate situation has led to an alarming rise in mental health issues for many Afghan women and girls. As their freedom to do anything beyond farming and household chores swiftly dwindles to almost nothing, many women and girls are losing hope. A Washington Post article detailing the crisis quoted Shafi Azim, a psychiatrist working in a mental health facility in Kabul, who explained: “They fear they will never be able to go back to work or school. They are isolated and become depressed.”1

CAI and our partners in Afghanistan are finding similar feelings among the women and girls in the regions where we work. “We used to enjoy going to school,” said Leila, a 17-year-old girl from the Badakhshan region. “But now we’re saddened because the schools are closed, and we can’t continue our studies.” Leila has to spend all of her time working in the fields and doing chores for her family. However, she has not given up her dream of one day restarting her education. “Our hope is for schools to reopen, providing opportunities for girls like us.”

Even amidst the sadness and despair, there are still many signs of hope and progress. Young women like Leila are holding on to the idea that one day they can resume their studies. And these glimmers of optimism are what keep CAI and our partners going—determined to do whatever we possibly can to keep hope alive for women and girls.

One of the most important things we can do is to provide education to primary school children, particularly young girls living in the most remote parts of Afghanistan. With the help of our donors, CAI continues to open and support community-based schools—local facilities in small rural villages that are converted into classrooms.

In 2023, we helped establish 252 classrooms, including providing furnishings and learning materials like pens, pencils, and notebooks. Through these schools, we’ve helped 7,700 primary school students—5,360 of them girls—get an education. We’ve also offered essential training to 191 women and 72 men to teach at these schools, giving them opportunities they would not have had otherwise.

One of our partners in this critical effort is WADAN, a local NGO that has been working to bring educational opportunities to all 34 provinces of Afghanistan for close to 20 years. With CAI support, WADAN currently supports 93 community-based schools in Badakhshan province in the country’s mountainous northeast. WADAN recently visited several of these schools to hear from teachers, students, and families.

Anas is a young boy from the village of Dehqan Khana who wants to grow up to be an engineer. While he is grateful for his school and the chance to learn, he is cognizant of all the children in his country who don’t have the same opportunity. “We request from WADAN that it increase the number of schools, so uneducated people can study,”

he said.

This little boy isn’t the only child with an impressive grasp of the needs of others and the desire to help his fellow community members. Several boys say they want their older sisters and female friends to be able to study as well. And many of the young people—boys and girls alike—express the desire of becoming a doctor.

“When I first joined this class, I couldn’t read or write, but now I’ve learned and made wonderful friends,” said Farzaneh. “I aspire to become a doctor and serve my community, as there are no clinics or doctors in our area, and people are in need.”

Some harbor the dream of becoming a teacher, so they can pass on their knowledge to their community. Zakia was able to fulfill that dream and is currently working as a teacher at a WADAN school.

“I’ve been teaching for two years, fulfilling my lifelong dream of becoming a teacher to pass on knowledge,” said Zakia. “Afghanistan’s situation is challenging due to ongoing conflict, but education offers hope for a brighter future. We hope the gates to girls’ education will reopen, as it increases literacy rates and empowers girls to graduate from schools and universities.”

Another teacher, Basira Ahmadi, echoes that sentiment. “This marks my second year of teaching at the school, and I’m delighted to see my students’ progress,” she said.

“I aim to be a successful contributor to society. I call on the international community to support girls’ education, and I urge the government of the Islamic Emirate to provide education for girls. Many children still lack access to education, and I hope the WADAN office can establish more schools.”

The people of these villages are keenly aware of all they have lost, and they yearn to give women and girls the opportunities they once had. But they have not let their struggles and disappointment darken their hopes and dreams. They continue to take advantage of the community schools they do have, and to pursue the educational careers available to them. They ask the international community—those who care about their plight and recognize the value of education—not to lose hope either. The people of Afghanistan are counting on all of us to continue providing support, so that one day, they can restore their rights and freedoms and fully achieve their dreams.

By Shahzadi Imrana Jalil, Moawin Foundation

When Ayub was a boy living in Haiderabad, a remote village in the mountainous Gilgit-Baltistan region of Pakistan, he attended a primary school supported by CAI. Back then, the Haideria Central Asia Supporting School had no actual building, no walls, and no washrooms. While it lacked the basic infrastructure one would expect of a formal school, what it did have was the dedication and passion of caring teachers, who not only taught Ayub the basics of reading, writing, and math but also inspired him to become a teacher himself.

“I remember there was a teacher named Sir Nazeer, who had a very positive impact on me,” recalled Ayub. “He used to teach children with a lot of love and advised us to work steadily each day.” Another vivid memory that stands out for Ayub is the cricket tournaments the school would organize. “We were quite excited about it, and this made us look forward to going to school.”

Ayub acknowledges that when he was a student, the school lacked many of the facilities and tools children need for an optimal education. But for him, it was enough to get him to continue his education through secondary school and earn his bachelor’s degree. He was so grateful for his experience that he decided to return to his hometown and teach at his old primary school, hoping to give his students the same kind of transformational education he had received.

Due to the continued support of CAI and its partner, the Moawin Foundation, the Haideria School is drastically different today than it was when Ayub was a boy. “There’s a proper boundary wall, and the school building looks beautiful,” he said. And while his teachers mostly had just a basic education, today’s teachers often have advanced degrees. Ayub’s students also have the advantages of internet access and e-learning, which offer a plethora of new tools and resources to broaden their education. Ayub notes, however, that so much more is needed. “In Pakistan, there’s simply not enough budget allocated for education,” he laments. “The education budget should be higher so that children can conduct experiments, visit labs, and become more creative.” He notes that his syllabus often requires him to conduct activities without the proper materials. “For instance, in the science book, there are topics related to chemistry that involve creating solutions. To carry out experiments like checking pH using pH paper or teaching hydrogenation, we require specific items.”

Ayub is grateful for the way CAI and the Moawin Foundation have stepped in to provide meaningful education and proper schools to supplement what the government is able to offer. He is also appreciative of the professional development support he’s received that has helped to improve his teaching skills. “We received a five-day teaching training where we learned how to teach, manage a classroom, create lesson plans, and understand the principles of Bloom’s taxonomy,” he explained. He and his colleagues were also taught about holistic child development, preserving the environment, mitigating climate change, dealing with child emergencies, and first aid response.

Ayub’s daily routine demonstrates his strong dedication to teaching. “Before heading to school in the morning,

I prepare the lectures to ensure that I am confident while presenting in front of the students,” he said. “When students understand what they are taught, they respond actively. They attempt to solve questions on their own, which brings me immense joy. This continues throughout the day. Later, I tend to some tasks at home, and in the evening,

I also provide tutoring. This way, my day comes to an end.” While his workdays are long, Ayub shows no signs of letting up. For him, his job is just too critical not to give it everything he’s got. “I believe that we are currently in an era of intense competition,” he explained. “Every teacher should strive to make their students highly capable, preparing them to face future challenges successfully.”

KEEP UP WITH THE LATEST NEWS

Sign up to receive updates and stories from the field.

Privacy Statement | Copyright 2025 Central Asia Institute. All rights reserved. Site Map

CAI is a U.S.-registered nonprofit 501(c)(3) organization, EIN #51-0376237. Contributions may be tax-deductible in the U.S.