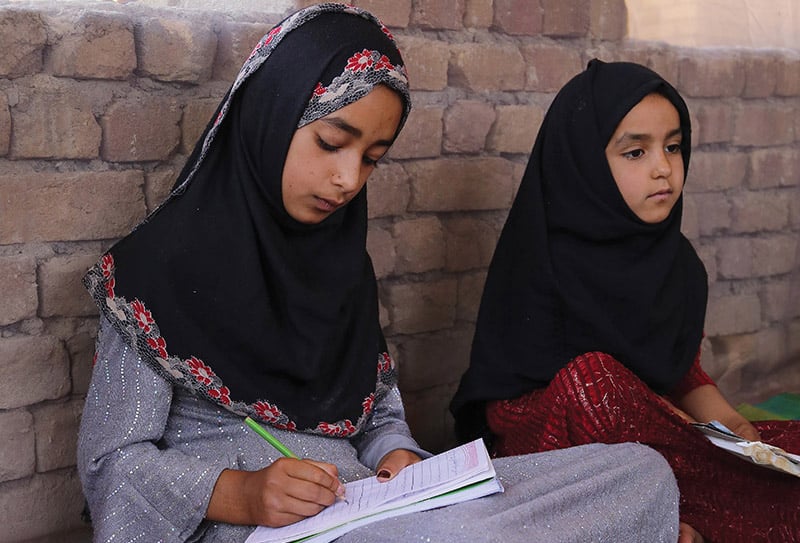

Against all odds, many Afghan women and girls are still getting an education

By Hannah Denys

Women and girls are standing up to Taliban rules and demanding access to education in hopes of a better future.

Angiza, an eighth grader, puts on her school uniform every morning, finds a quiet corner in her house, opens her books, and studies by herself. She breaks for lunch, then returns to her books until what would be the end of a normal school day in Afghanistan. Even though the Taliban has closed schools for adolescent girls like Angiza, she is not putting down her books or lessons. Even if she must do it alone, she is determined not to give up her education.

Across the globe, women and girls like Angiza are losing their basic freedoms. Nowhere is the threat more daunting than in Afghanistan, where the Taliban, back in power since August 2021, is attempting to not just repress girls and women, but to render them invisible. In a series of oppressive and misogynistic rulings during its first year back in power, the Taliban has attempted to destroy the lives of women and girls by denying their rights to education, employment, and free movement. It has decimated the country’s system of protection and support for women fleeing domestic violence; beaten or imprisoned women and girls for protesting new restrictions; and contributed to a surge in the rates of child, early, and forced marriages.

Topping the list of human rights being targeted by the Taliban is access to education. An uneducated population serves the Taliban’s agenda. Uneducated women are less resistant to staying at home and remaining illiterate and subservient. Uneducated boys and men are fodder for recruitment. A girl with a book or a professional woman unafraid to speak out in protest undermines the Taliban’s power.

“These draconian policies are depriving millions of women and girls of their right to lead safe, free, and fulfilling lives,” said Agnes Callamard, Amnesty International’s secretary general. “Taken together, these policies form a system of repression that discriminates against women and girls in almost every aspect of their lives. Every daily detail—whether they go to school, if and how they work, if and how they leave the house—is controlled and heavily restricted.”

Amnesty International reports that rates of child, early, and forced marriage in Afghanistan are surging under Taliban rule. Destitute families are being forced to marry off their daughters in exchange for a “bride price.” In a country suffering from widespread hunger, where 90% of the population now lives in poverty, one less child at home means one less mouth to feed.

But the people of Afghanistan are not giving up on their quest for an education. They know that providing an education to both boys and girls is not only their child’s best chance for a better life, it’s also the best hope for the future of their family and their country.

Then and now: 20 years of progress at risk of unraveling

Afghanistan has made huge strides in educating its youth over the last 20 years. Back in 2001, when the Taliban’s last rule ended, virtually no girls were enrolled in school. In August 2021, when the Taliban took back control and the United States withdrew from the country, 3.5 million girls were enrolled in school. During that 20-year span, literacy rates among girls doubled from 20% to 40%.

Without the international community’s continued support for education, these hard-fought gains could be lost, and the next generation of Afghans, especially women, could lose out on education altogether.

“Education is hugely important to the future of Afghanistan,” said Alice Thomas, executive director of the Central Asia Institute. “With 63% of the population under 25 years of age and 46% under age 15, education has the potential to one day save the country from endless cycles of conflict and repression.”

CAI’s community-based schools keep education alive

Over the past two decades, CAI has worked to make education possible, especially for girls living in impoverished, rural areas where more than half of girls were out of school even before the Taliban regained control. Our focus is on those remote communities with the largest number of out-of-school children.

Because there is often no government-run school in these areas, CAI’s approach is to bring education directly into the heart of these communities by establishing community-based schools. The community-based model means classes are held in the home of a village elder, in a mosque, or in a similarly safe space in the village. Involving the community is imperative. A council comprised of members who are elected by the people of the village recommends teacher candidates and monitors the school. Because the council has agency over how the school is run, the members take ownership in making the program a success. If problems arise with the Taliban, the council does the negotiating.

“In many ways, CAI’s approach of working through local partners and engaging the local community to ensure buy-in has helped us adapt to the new challenges,” Thomas explained. “The communities themselves drive the demand for education, and when obstacles arise with the Taliban, they are willing to go to bat for their children.” It takes tremendous courage to stand up to the Taliban, yet ordinary Afghans are fighting back, demanding education for their children, including their daughters.

Even though some council members may not be able to read and write, they recognize education as their children’s only hope of one day moving on from a life of hardship and struggle. They’re passionate about defending the program that is educating their children. This past year, CAI employed the community-based school model to provide education for approximately 5,700 children, primarily girls, in grades one through three in nearly 200 rural communities across five provinces. Next year, CAI hopes to increase that to 250 community schools that will serve approximately 7,500 children, primarily girls.

CAI is also piloting projects to reach adolescent girls whose schools the Taliban has refused to reopen. Again, the approach is to work closely with the community to recruit teachers and find a place to hold private lessons for the girls. Another project involves recruiting older high school girls to become teachers for the younger classes. The programs are in high demand among parents, communities, and the girls themselves. CAI is now working with its partners to expand these classes in 2023 to reach even more adolescent girls and help ensure their education and path to a better future are not taken away.

“We’re slowly making inroads—one girl, one boy at a time,” said Thomas. “Positive change is possible if the population is educated.”

In 2022 CAI supported

191 community-based schools across five provinces,

serving 5,700 children, primarily girls.

CAI’s 2023 goal is to expand the number of community-based schools to 242

and educate 7,500 Afghan children.

Education changes a girl’s life

Over the past 20 years, a whole generation of Afghan women have been educated. Their enormous contributions to their families’ welfare and to Afghan society have led to a shift in public attitudes towards girls’ education, and not just in urban areas. Data collected by UNESCO, World Health Organization, UNICEF, and other organizations show a remarkable improvement in the life outcomes of an educated girl and the choices she makes compared to her uneducated counterpart. Today, a large majority of Afghans—87% according to a 2019 survey by the Asia Foundation—support girls’ education.

The ability to earn an income is one incentive for getting an education, but there are many more. An educated young woman marries later. She’s older when she has her first child, and she’s likely to have fewer children. Because she sees how much better her life is than the life of her uneducated mother, she is determined to send her own children to school, especially her daughters.

An educated mother can find work and earn income, which means the family has a place to live and food to eat. Her children are healthier. And when a child gets sick, the family can afford medical care. On every measure of quality of life, including health outcomes, personal safety, and economic indicators, educated girls surpass girls who never had the opportunity to go to school.

“In a country riddled with chaos and poverty, education gives girls and women a fighting chance,” said Thomas. “It offers a ray of hope—a beacon pointing to a better life. Education gives girls and women the power to make their own decisions, earn income, and contribute to the well-being of their families, communities, and country.”

At a time of crisis, Afghan women provide hope and inspiration

“Many things give me hope about Afghan women,” said Duniya Stanikzai, former deputy director of Shining Star, one of CAI’s partners in Afghanistan. “Afghan women are not the same as they were 20 years ago; they have changed. Back then, women were silent and afraid and accepted whatever the Taliban said. Now they’re finding ways to create opportunities for themselves.

“Girls in secondary school who can no longer attend classes due to the Taliban’s restrictions are learning online or in secret schools,” said Stanikzai. “That women are finding ways to work around the Taliban indicates how desperate they are to educate the daughters and adult women in the family. We don’t want the Taliban to win.”

CAI is committed to standing with Angiza, Stanikzai, and so many other courageous Afghan women and girls like them who are fighting for their lives. Never before has CAI played a more important role in their futures.

“Education changes lives, protects futures, unites communities, and kindles hope,” said Thomas. “These are enormously challenging and deeply troublesome times for Afghanistan. But we’re adapting and adjusting our programs to provide education to youth. With your help, we will continue to give girls and women the one thing that no one, including the Taliban, can take from them: an education.”

A $100 donation sends an Afghan child to school for an entire year.